Tutorial on building a single panorama image from a video can help with verification in order to protect from repeatedly viewing the most traumatic parts of a video

Tools needed: Screengrab tool [such as Jing], presentation software package [Keynote, Powerpoint, Google Slides or similar], open source satellite imagery from Google Earth Pro or satellite mode of any mapping tool that is available

Skill Level: Basic

Anyone with a smartphone, an internet connection and a social media account can film a human rights violation. It’s why open source information has become so useful for human rights investigations at Amnesty International.

Yet scenes from remote locations need to be verified – especially if we cannot get there in person. This requires us, painstakingly at times, to go through a collection of videos to work out exactly where and when something happened.

These videos are mostly filmed by amateurs who happen to be at the scene of the event – who themselves may be frightened or at risk. This means that the quality can be poor, with fast movements, shaky hands, dropped cameras, overexposure, underexposure, low camera pixel quality and other flaws.

Couple this with the fact that amateur filming a video of any violent act — such as the unlawful killing of a civilian in conflict, torture, or police brutality — can be traumatic to watch, especially repeatedly.

Building a panorama of the video can allow the investigator to repeatedly look at the surrounding topography needed to geolocate a scene, without being subjected repeatedly to the potentially traumatic images in the video.

This is how we geolocated a video from 18 March 2019, that showed the aftermath of a US air strike hit in Somalia’s Lower Shabelle region. The strike killed three farmers returning from their farms to their homes in Mogadishu, Leego and Yaaq Bariwayne.

A brief look at this video – which we have edited to not show the bodies of those killed in the strike – shows that it moves quickly, but a large landscape is visible. This is key to geolocating the video – but requires repeat viewing to find the precise location in a remote region of Somalia.

Creating the panorama took time, but was worthwhile in the end. While there are several tools on the market that claim to be able to do this, it was quicker and more precise to carry this out by taking screen grabs of the video and placing them in a presentation software package. We used Keynote, but it can also be done in Powerpoint or Google Slides.

To take screen grabs of a video we recommend the free tool Jing created by Techsmith. This allows you also to annotate screenshots to highlight features.

This is the procedure we followed:

1. Go through the video frame by frame [in VLC or QuickTime player – you simply use your cursor to do this]. Every time there is a large change in scene, take a screenshot.

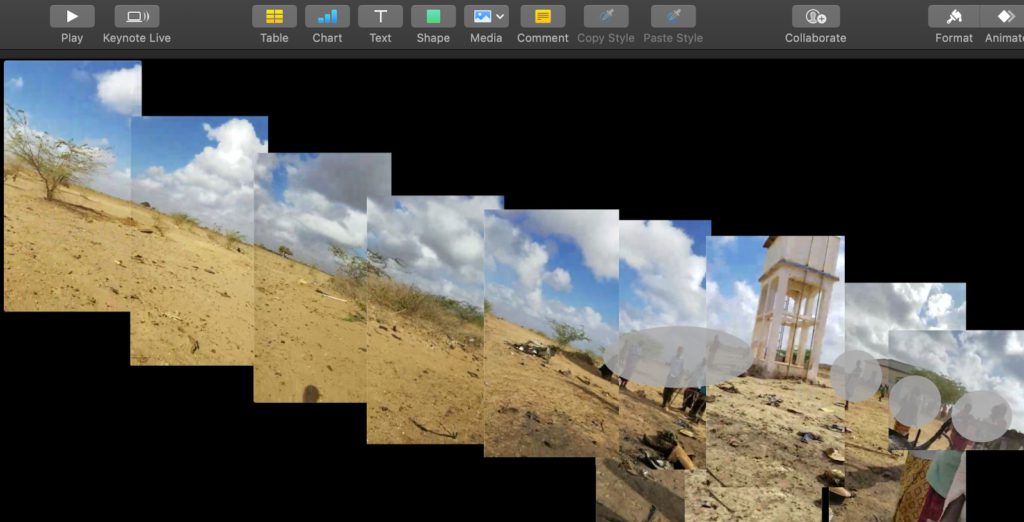

2. When enough images are collected, import them all into your presentation software package.

(Images imported into Keynote on Mac)

3. Then take time to sort the images into the panorama.

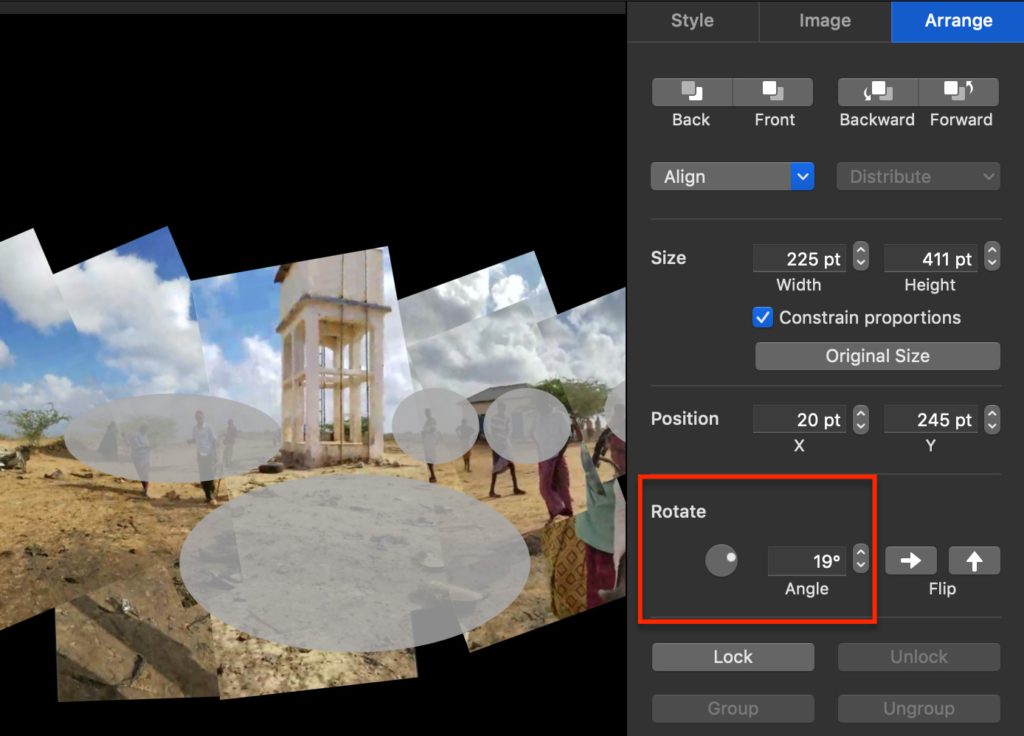

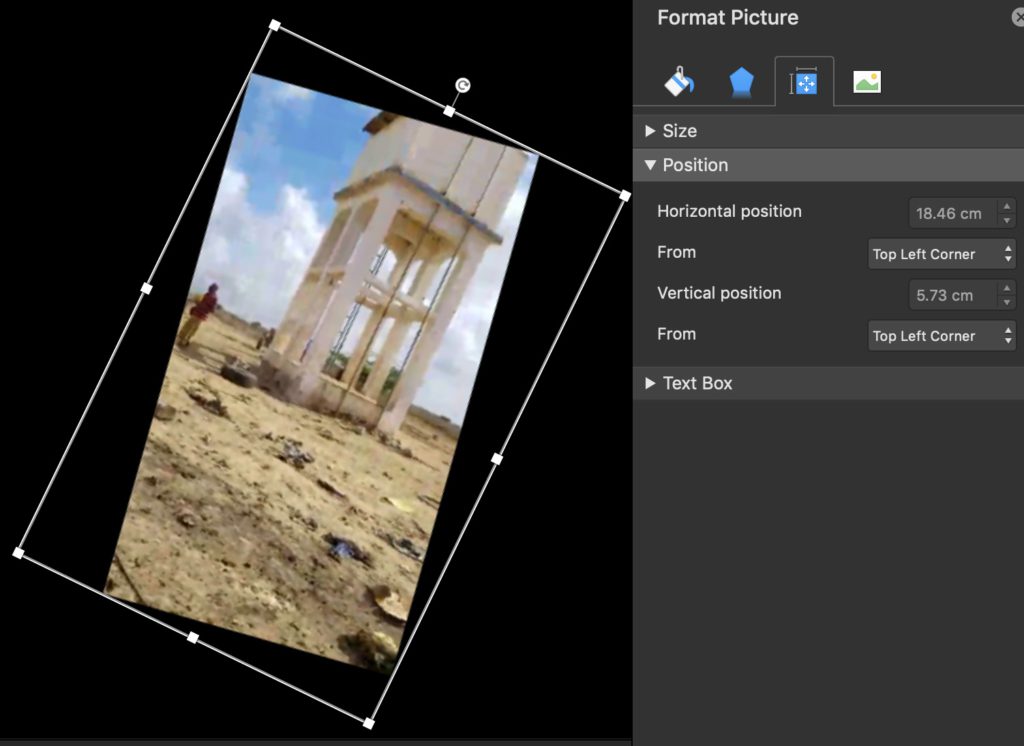

4. Remember that the earth is not flat – so playing with the angle of the images can help. There is a rotate tool in Keynote where you can shift the images as needed.

Keynote (above) and Powerpoint (below) options for rotating images

5. With a small amount of shifting and rotating, you can build a full panorama of your video, to avoid repeatedly viewing the worst elements of the video.

With the panorama you can use open source satellite imagery to geolocate the event, which we explain further in other tutorials on this site.

To quickly summarize what we did; the water tower and blue-roofed structure stand out in the image. With a general knowledge of the region the video came from, and Google Earth Pro you can pinpoint the tower in relation to the blue-roofed structure. Then you can also align the trees surrounding the structures, concluding and confirming exactly where the air strike hit and killed the three farmers – giving more weight to the research findings.

For this specific case, Amnesty also interviewed 11 people – in person and remotely – about the 18 March strike, including family members, those who visited the scene, and staff at Hormuud Telecom, a company where one of the men also worked. In addition, we also assessed media reports, US government statements, vehicle purchase records, official IDs and medical records. All of these pieces of evidence lent weight to and helped create a solid case, allowing us to document a human rights abuse that happened in a location to which Amnesty had no physical access.