On 28 June 2019, an aircraft bomb fell on a family home in the village of Warzan, near Ta’iz in southwestern Yemen. The detonation collapsed the front of the home, the pancaking floors killing six civilians inside, including three children, aged 12, nine, and six. Fifteen minutes later, a second strike hit the structure, the pilot returning to ensure the home was destroyed.

When family members returned to the scene, they found munitions scrap, pieces of the bomb that had survived the explosion. But they were badly scraped and damaged, and most of the identifying marks had been removed by the blast.

Despite this, we in the Evidence Lab were able to identify not just the specific munition used, but also the manufacturer. How did we do this? By comparing this fragment to many others we have already successfully identified.

When trying to research a weapon used in an attack, an investigator is usually not starting from scratch, considering every type of ordnance ever manufactured. Since the invention of modern explosives and fuzing systems after the First World War, thousands of models of munitions have been produced, a truly overwhelming encyclopaedia for any researcher to page through. Instead, every conflict has certain munitions that – whether because of local manufacture, import, or illicit diversion – are regularly used by the warring parties. The US military calls this the ‘ordnance order of battle.’ You could also call them the Usual Suspects.

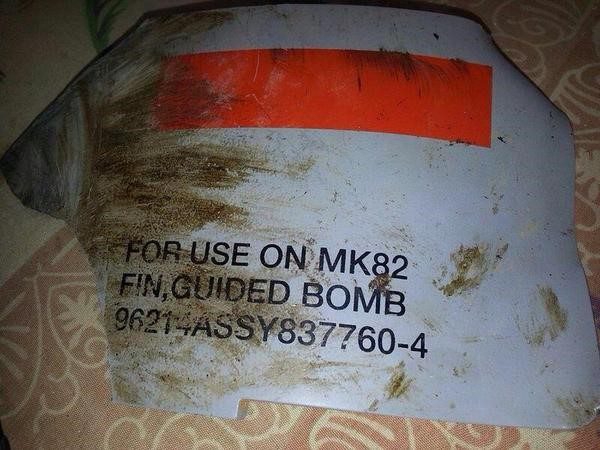

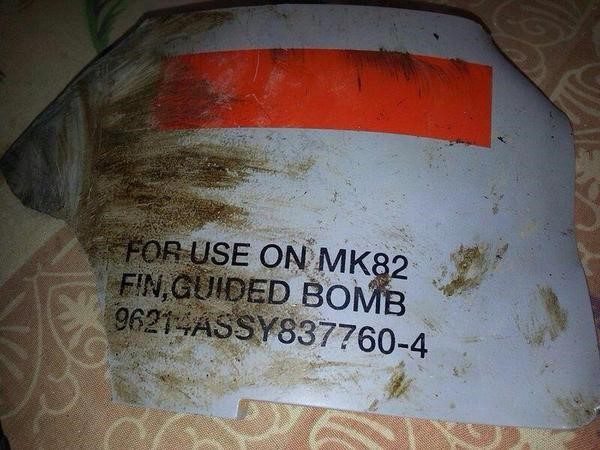

Amnesty International and other investigators have identified clear trends in the use of laser guided bombs by the Saudi Arabia- and Emirati-led coalition in Yemen.The piece of scrap found in this case in Warzan consists of a grey fin with an orange stripe, a telltale part of a Paveway II 500 pound bomb that often survives detonation. But to confirm this, we usually want to consult the writing stenciled on the side of the weapon. On this particular piece there were not many legible numbers and letters for us to look up, so we had to work backwards, based on what we already know about the ordnance used in Yemen.

These Paveway IIs, also called GBU-12s, are made by two different American manufacturers, Lockheed Martin and Raytheon. All US government contractors are uniquely identified by their Commercial and Government Entity (CAGE) codes: 94271 for Lockheed Martin, or 96214 for Raytheon. Helpfully, both contractors print their CAGE codes on the fins of the Paveway IIs they produce. The bottom of the scrap from Warzan has some readable writing: a “9,” then an unreadable digit, and then “21”. Or maybe “27”? It is hard to tell for sure, until we compare it to other scrap.

Here, in the photo and video screen shot, are two other GBU-12 fins from other strikes in Yemen:

Here we can clearly see the CAGE codes for Raytheon and Lockheed Martin. Note, however, that each use a different ASSY, or assembly number, to identify this same specific part. Raytheon uses an ASSY of 837760-4, and Lockheed Martin uses 147214.

Comparing these pieces again to the scrap from the recent strike in Warzan, we can see the “37760” in the correct position. Therefore, we are able to conclude that not only is this a GBU-12, but that it was manufactured by Raytheon.

When conducting weapons investigations in a human rights context, the goal is to hold a state or armed group accountable for violations. In this case, by identifying the manufacturer of the GBU-12, we can provide additional evidence that the USA needs to halt the sale of US-made weapons to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates for as long as there exists a risk that they will be used in war crimes and other serious violations, a major advocacy call for Amnesty International.