It has been three years since an estimated 740,000 Rohingya fled the Myanmar military’s targeted campaign of violence in Rakhine State for refugee camps in Bangladesh. Yet for the Rohingya remaining in Myanmar, life is still full of danger and human rights violations continue. In January, as part of an ongoing case about alleged genocide by Myanmar, the United Nations’ top court issued an order for the Myanmar state to protect the Rohingya. Yet, as we did in 2017, Amnesty International continues to receive video and photographs depicting human rights violations in Rakhine State. This blog will explain how we verified the location of some of the video footage Amnesty International has recently received, and how it shows the extent to which human rights abuses continue against the Rohingya today.

In 2017, researchers from Amnesty International were on the ground in Cox’s Bazar in Bangladesh – the destination for many of the Rohingya refugees. We interviewed people in the camps, giving them space to tell their stories. We also verified evidence in the form of videos they brought with them on their mobile phones, using satellite imagery to corroborate what we were hearing. This led Amnesty to call the systematic violence ‘crimes against humanity’. The International Criminal Court launched an investigation, and the UN Human Rights Council established the Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar The Myanmar government became a pariah on the international stage.

But since then, monitoring has become even more difficult. One of the reasons for this has been a prolonged mobile internet blackout that has lasted more than 12 months in many townships of Rakhine State, and continues with limited 2G services. Where connectivity exists today, it is slow or useless. However, video evidence acquired, verified, and released by Amnesty shows that the situation on the ground in northern Rakhine State is still dire. Indeed, Rohingya who did not flee across the border to Bangladesh are a people still under siege. They are under siege from their government, which has not dismantled the apartheid regime that governs every part of their lives. They are under siege from conflict, as the Myanmar military continues to clash with a Rakhine ethnic armed group called the Arakan Army in bloody battles, leaving civilians from various minority groups, including Rohingya, caught in the crossfire. And they are under siege from the COVID-19 pandemic threat, in a state where they already face shamefully unequal and inadequate medical services. In addition, Myanmar is also changing the landscape in parts of northern Rakhine State in ways that will make it even more difficult for Rohingya refugees to return home.

The evidence that we have released to mark this three-year anniversary comes from activists in northern Rakhine State who take risks every day to film these developments. These videos show Rohingya deaths, corruption, and new administrative structures going up on land owned by Rohingya. This content, filmed in 2020, was given to Amnesty’s Crisis Evidence Lab and Amnesty’s Myanmar research team, which has worked together to independently verify it.

This verification process is always important – in Myanmar, it is common to discover content from previous events circulating with the claim of depicting recent atrocities. Additionally, as much of the content has been filmed by individuals taking huge risks, the security of these individuals is paramount. In many of the instances, we cannot reveal when and when they were filmed. However, in the case of one video from close to the village of Nan Yar Kone in the Kun Taing village tract of Rakhine State’s Buthidaung Township, we can.

Video evidence of land grabs

The video in question shows a building site. We were told by activists that it shows the building of a new government technical college on Rohingya-owned land. But, from afar, how do we confirm that this video is indeed filmed near the village of Nan Yar Kone, and is filmed recently?

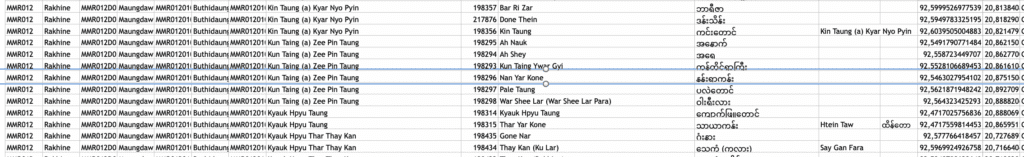

The first step in this process was to find out if the village actually exists, and if so, find out its geo-coordinates. The Myanmar Information Management Unit has an established database of names and locations of many villages and townships.

Downloaded as a spreadsheet, the file is a large and unwieldy one, but by spending some time understanding it, finding the geo-coordinates of named villages in Myanmar becomes relatively straightforward.

Nan Yar Kone, Kun Taing Village Tract

We could find that the village of Nan Yar Kone does exist in the Kun Taing Village Tract (a village tract is a subdivision of Myanmar’s rural townships) in Buthidaung Township. The name at least matches what our sources told us. Nan Yar Kone has the coordinates 20.875150, 92.5463027.

Google Earth Pro

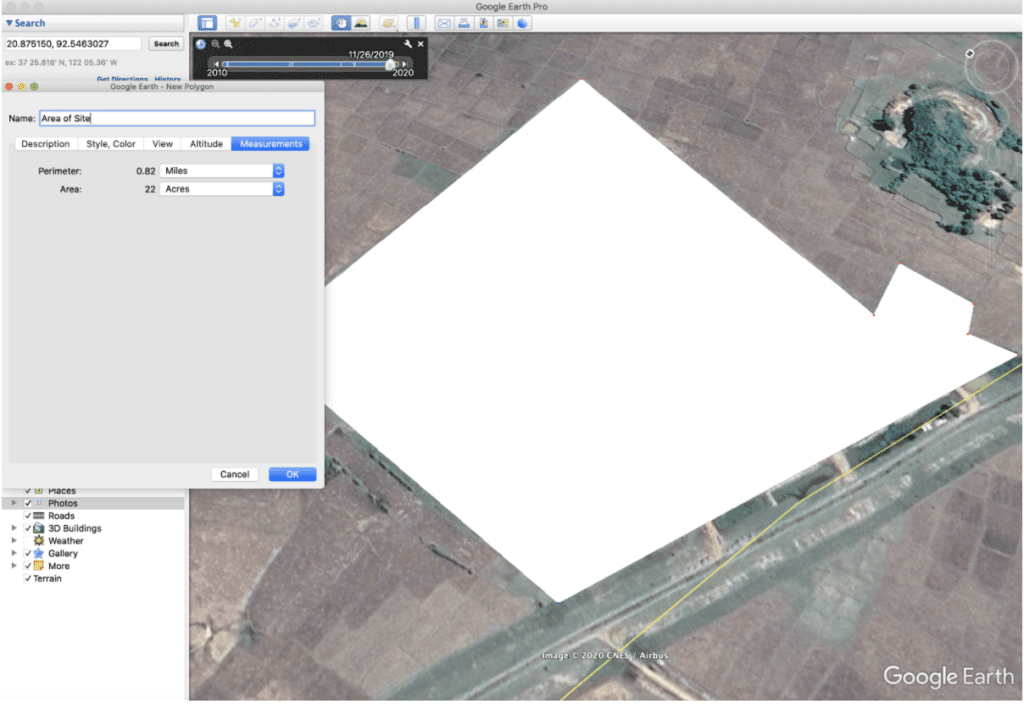

However, just finding the name of the village and its geocoordinates is not enough to confirm the location of the video. By putting the coordinates into Google Earth Pro, we were able to go and study satellite imagery of the village. Just to the east of the village, we can see what appears to be a construction site.

But was this site new? To figure this out, we used the historical imagery feature on Google Earth Pro. Going back through the historical imagery, we could see that the site has been worked on since September 2019, with the land lying empty in 2017. However, there is no imagery available between 2017 and 2019 – so a precise date for the start of construction here could not be seen. We’ll come back to that shortly…

Do the buildings match?

The next step was to confirm that the buildings match. In the video – that we were told was filmed in January 2020 – we can see three main structures. These buildings all correspond to the satellite imagery.

A closer look at the building on the far left shows a blue roof visible in the satellite imagery from March 2020, but not in the imagery in November 2019. The satellite imagery gives us a timeframe that the video was shot in – which confirms what we were told.

When did construction start?

As mentioned above, the historical imagery could only take us back to September 2019, after construction had already started. So how can we find out when the actual construction began? At Amnesty’s Crisis Evidence Lab, we were able to use our partnership with Planet Labs to use lower resolution imagery to discover that construction started between 28 March and 3rd April 2019.

Further evidence

The next step is to discover further information that may be publicly available. A collection of simple Google searches using key terms brought up a story published in the website The Stateless in February 2019, stating that over 20 acres of land have been taken in Nan Yar Kone to build a ‘Government Technology High School’. First of all, as with all sources, we approach this information through the lens of verification. In this article, one piece of information stands out – that over 20 acres of land had been seized to build the college.

On Google Earth Pro, it is possible to make out the borders of the construction site. By using the measuring tool on Google Earth Pro, we can measure its area. In this case, that means the acreage of the site. By using the polygon tool, we can measure the border fence of the site, which gives us 22 acres – a close match with the data in the article.

Ethical considerations

In the video published today, we depict several of the human rights violations that Rohingya communities are still experiencing in Rakhine State. Many of the videos we received – amounting to nearly two hours’ worth of content – showed the immediate aftermath of the explosion of artillery or landmines, of arson in villages, of displacement, and of extortion. We carefully selected imagery to tell the story of what is going on today in northern Rakhine State – without revealing identities, or putting the people in these situations at excessive risk – but we were also careful to consider the fact that people want their stories to be told to the world. While the plight of the Rohingya in Myanmar was headline news three years ago, it is far from the front page today. Telling these stories during a mobile internet shutdown, where people are taking risks to get videos and photographic evidence of human rights abuses, is difficult. We owe it to the courageous people taking these risks to share their stories. Ensuring that thorough verification is done throughout the process is key to getting those stories right.

With the general access problems that independent monitors have to Rakhine State – further hampered by the Myanmar government’s restrictions and the COVID-19 pandemic – monitoring events through video, satellite and all other forms of data are tools that add to our ability to collect evidence and hold the authorities in Myanmar to account.

The Rohingya cannot continue to wait for justice, and the international human rights community cannot turn its eyes away from their plight.