Over the past few months in the Evidence Lab, we have been thinking about how we document and share the huge variety of work we do. No two days are ever the same. Our work spans from reactive verification responding to emerging crises, to large-scale multi-month collaborations, to visualising research at the end of a project.

To experiment with how we communicate our work, three members of our team devised a writing exercise. We each picked a project, spent a few hundred words outlining our team’s contribution, and then compared how we wrote about our work. The outcome, documented here, gives a sense of some of the things we worked on in the second half of 2022, what we did, and why.

For a report on Myanmar, we brought together multiple strands of open source evidence to identify, connect and attribute multiple stages of the supply chain of aviation fuel to the Myanmar military with pinpoint precision. Communicating research in a compelling way is also a key part of our work: in December, we visualised a report on older people’s experiences of the war in Ukraine using a multimedia webpage and collages. Finally, to document protests in Ecuador, we used digital evidence to show what traditional forms of evidence could not; quickly building a detailed picture of the death of a protester.

A long-term collaboration: open source reporting on a complex case

In November 2022, Amnesty International published Deadly Cargo – a report that uncovers the secretive aviation fuel supply chain behind the Myanmar military’s deadly air campaign. To unravel this complex supply chain and examine how it impacted civilians in Myanmar, Amnesty International brought together the Business and Human Rights team’s expertise in corporate investigations and supply chains, the Myanmar country team’s deep knowledge of the conflict and connections to activists, and the Crisis Response Programme’s on-the-ground investigations into air strikes that killed or injured civilians. The Evidence Lab joined this months-long investigation to add enhanced digital investigative techniques that helped to piece together key parts of the situation. Together, we provided a detailed account of this supply chain – from the port where the fuel originally departs, to air strikes conducted by the Myanmar air force that amount to war crimes.

Our team used multiple methods to contribute to the investigation, including:

- Using satellite imagery to locate storage depots, confirm the arrival of fuel deliveries at sea, spot aircraft and confirm the damage of air strikes.

- Finding and verifying photos and videos posted to social media that provided evidence of air strikes that killed or injured civilians or destroyed civilian objects such as homes, schools, health facilities and religious buildings.

- Cross referencing flight spotter data that shows the movement of aircraft, including when specific fighter jets and helicopters departed for deadly attacks.

- Analysing photos and videos of weapons and ordnance used in the Myanmar military’s air campaign, including examining the damage to buildings and craters formed by air strikes. Notably, our report documented the first known cases of the Myanmar military employing cluster munitions, which are widely banned due to their inherently indiscriminate nature.

By combining these methods, our investigation showed how aviation fuel reached Myanmar, and how it was used by the Myanmar military to commit war crimes.

Visualising research: story page for report on older people’s experience of war, displacement, and access to housing in Ukraine

The Evidence Lab’s primary focus is producing new research. However, the team sometimes also joins investigations in their final stages to assist with the communication of findings. The results can be complex (see some of the 100 animations we generated for a report documenting the Taliban’s crackdown on women and girls’ rights in Afghanistan) or more simple, as was the case for a recent investigation into older people’s experience of war in Ukraine.

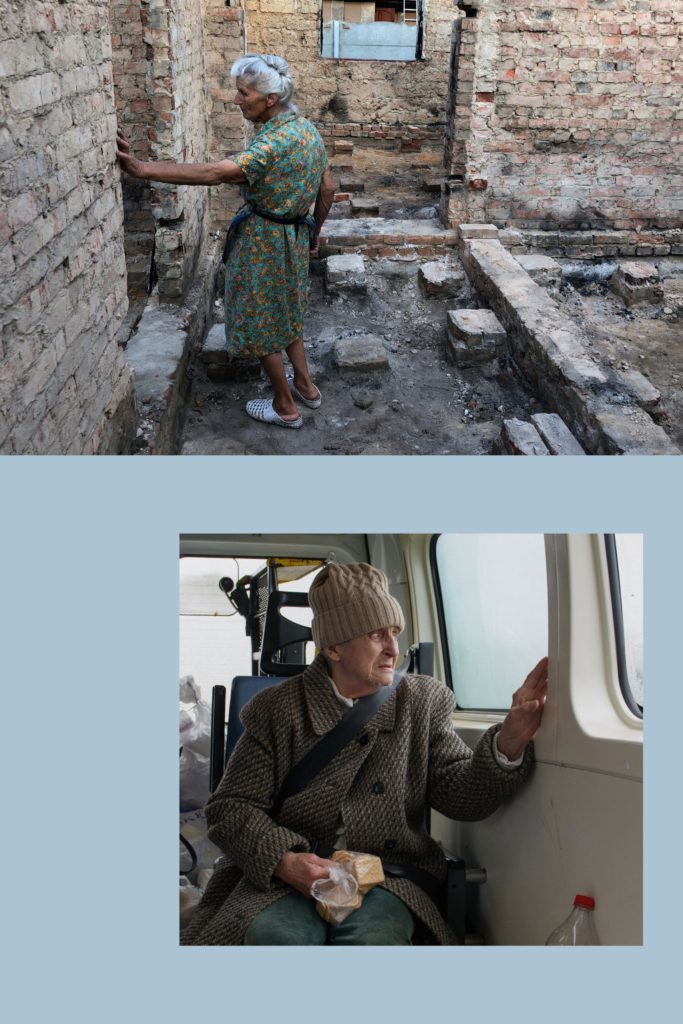

For this report, ’I used to have a home’: Older people’s experience of war, displacement, and access to housing in Ukraine, the Evidence Lab created what we call a ‘story page’, containing collages of the photographs taken during the research process, and a map showing where people had been interviewed.

Unlike an interactive gallery, collages show readers a collection of images at a glance. The format also allowed us to include a higher number of images, which worked well with the mix of professional photography alongside images taken by investigators on their phones.

Such projects are conducted in short sprints and are small interventions from our team, usually at the end of a months-long evidence-gathering and writing process. We undertake this work when we can, because we understand the importance of engaging and accessible communication, and that not everyone has the time to read a detailed in-depth report.

Reacting to emerging crises: verification of excessive use of force in Ecuador

On 21 June 2022, security forces repressing a demonstration in Puyo, Ecuador, fired a tear gas grenade directly and at close range at BG, a Kichwa Indigenous man from the San Jacinto commune. BG later died at the Puyo General Hospital from the shot.

The Evidence Lab supported the research of Amnesty International’s Americas Regional Office by finding and verifying digital evidence to complement testimony they had gathered. Within the team we have expertise on protest work, from tear gas and batons to in-depth analysis of specific protests, and we follow and regularly work on global protests. Collaboration with different researchers across Amnesty is also a part of almost every project we do. In this case, our specialised skills working with digital evidence supported and empowered their traditional research methods.

We sought to narrow down the location, date, time, and type of weapon used to help evaluate the circumstances of BG’s death. On social media, we found photos and videos of the injuries BG sustained, which helped to determine the weapon used (consistent with a tear gas canister) and location of the video (an area of Puyo, Ecuador known as Picolino). We also analysed public police and hospital statements to determine the date. To narrow down the timeframe, we used the fact that the videos were shot at night: we compared the earliest content posted from the incident, with the time of dusk on the day to give an hour-and-a-half window.