Earlier this year, the Crisis Evidence Lab published an article rounding up three different projects we worked on in the second half of 2022. As our work is so varied, we found it rewarding to share a small slice of what we get up to and so, continuing this format, here are three projects we have worked on over the past three months.

In this period, we’ve received 35 research requests from colleagues across Amnesty International, and worked on more than 15 countries. Weapons analysis was key to our continued verification work on protests in Peru; we supported the update of maps with contested borders for Amnesty’s Annual Report country pages; and the Digital Verification Corps (DVC) verified hundreds of videos of police violence against protesters to support advocacy in Amnesty International’s Global “Protect the Protest” campaign.

Weapons analysis: documenting excessive use of force by Peruvian law enforcement

Amnesty International has been closely following and raising awareness of the repression of protests in Peru, which began in December 2022. Starting in Lima, the protests soon spread to various other parts of the country, including localities such as Ayacucho, Juliaca, Puno and Andahuaylas. A total of 49 people died in the context of police and military operations due to repressive actions carried out during the months of December 2022 and January and February 2023. In close partnership with Amnesty’s Americas Regional Office, members of the Evidence Lab analyzed nearly 92 videos and images relating to violent police repression.

In this project, the digital evidence would provide first-hand evidence of the nature, scope and misuse of force during protests, as well as strengthen existing cases documented in testimony gathered by the researchers both remotely and in the field. Therefore, it was most important to verify the date and location of each incident, and analyze any misuse of force.

Among the videos analyzed by the Evidence Lab is a 28-second clip that shows the last moments of the life of John Erik Enciso, an 18-year-old inhabitant of Andahuaylas. The video shows three young men (in addition to the camera holder), two of them progressing on a hill track while gunshots are heard in the background. A person in a pink sweater is seen from behind walking along the hillside, before falling to the ground.

This pink sweater was important in helping us confirm the identity of the person who’d been shot as John Erik Encisco: the jumper exactly matched autopsy photos of the young man’s body. We were also able to match the trajectory of the bullet described in the autopsy report with the entrance wound and position of John Erik Encisco as seen in the video.

Once we knew the individual’s identity, we focused on the date and location. A reverse image search showed that the video was first posted on social media on December 12, during a day of protests in Andahuaylas. This, alongside the weather and other context from the video, confirmed what was described in his family’s testimony and the autopsy: this is a video of John Erik, and he was killed on December 12.

Geolocation was initially difficult, as the background is relatively blurry and the video mainly focuses on John Erik and his immediate surroundings. Using the building patterns, riverbed, topography, and electric poles which can briefly be seen, we could confirm that the video was captured on Cerro Huayhuaca hill.

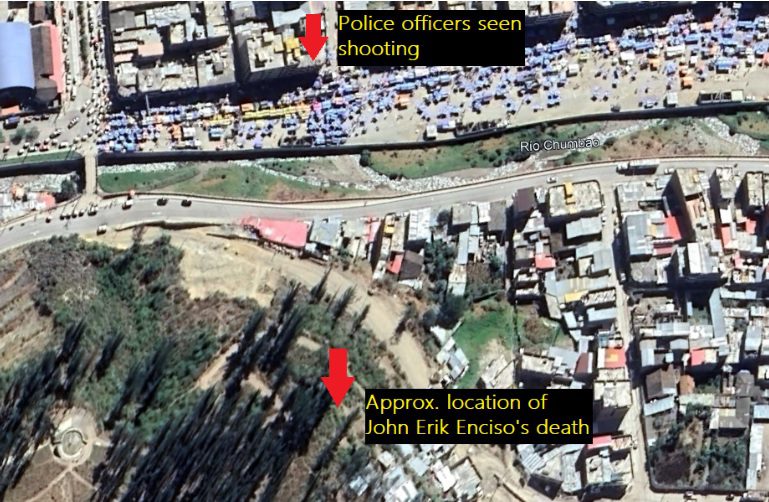

The date, time location information we’d gathered then meant we could link the video clip to another video of the events in Andahuaylas, also captured on December 12, where policemen are seen shooting at off-screen targets from the roof of a building, at the intersection of Ejército Avenue and Cesar Vallejo Avenue.

Forensic reports support the theory of a shot originating from the area facing the hill, including, potentially, from the rooftop area, on the other side of the Chumbao river. The unspecified projectile entered John Erik Enciso’s body from the back of his left shoulder and exited the front, ending its course in his neck and skull, following an ascending left-to-right trajectory.

This case illustrates how the Evidence Lab collaborates with Regional Offices and researchers in the field, combining data sources to show human rights violations we otherwise couldn’t prove. In this specific case it allowed us to reconstruct, in detail, what likely amounts to an extrajudicial execution by police forces in Peru.

Geospatial techniques: creating country maps for Amnesty.org

In 2021, Amnesty International decided to use location maps on the organization’s website country pages, where the research and campaigns on human rights issues is published. The Evidence Lab was brought in to assist in this large endeavor of creating more than 150 maps.

The Evidence Lab works with geospatial information on a daily basis and is involved in producing many of the research maps. When approached to help support this work, the first major question was choosing the projection, meaning the method for representing the three-dimensional globe on a two-dimensional surface.The second major question broached was that of borders. Many countries have disputed borders, with some creating friction impacting local populations more than others.

Since it is impossible to accurately represent the Earth in two dimensions without distortions in distance, direction, scale and area, there are thousands of projections developed depending on the attribute one needs to best preserve in that specific map. Entire courses can be dedicated to projections and if you receive geospatial data in different projections and try to overlap them, it can create major inaccuracies. This question of projection was presented to a larger group within Amnesty which prompted some very thoughtful responses including the recommendation to flip some countries upside down (yes, looking at the world with the north-up is not scientifically backed).

South up map with Equal Earth projection.

After much deliberation, we settled on regionally specific Lambert Conformal Conical with north-up, where directions, angles, and shapes are maintained at infinitesimal scale. This is not available through many online map generators like Mapbox, maps.me or even Google Maps, and required the skills of a GIS professional to ensure accuracy and efficiency in creating all of the maps. If you compare our map of Canada to that of Google Maps and Google Earth, you can clearly see some differences, especially when focused on Greenland.

The complicated discussion of borders and disputed boundaries orders arose next. Our process was to request feedback from Amnesty International offices working in contested regions – such as India and Pakistan – and received varying results. The default , in the end, was to follow the UN standards for representing borders.

Using Visual Evidence for Advocacy: Mapping Problematic Use of Less Lethal Weapons in Protests

The right to protest is under growing threat around the world. State authorities are implementing an expanding array of measures to suppress organized freedom of expression. In response, Amnesty International launched a global multi-year campaign “Protect the Protest” that aims to challenge attacks on peaceful protesters. As part of the campaign, Amnesty also advocates for improvement in legislation, as well as for the introduction of new laws that will protect the right to life. Together with 30 other civil society organisations, we are calling for the creation of a new United Nation backed instrument, a Torture-Free Trade Treaty. The treaty proposal is aimed at prohibiting the manufacture and trade in inherently abusive law enforcement equipment and controlling the trade in equipment that can be used for torture and other forms of ill-treatment.

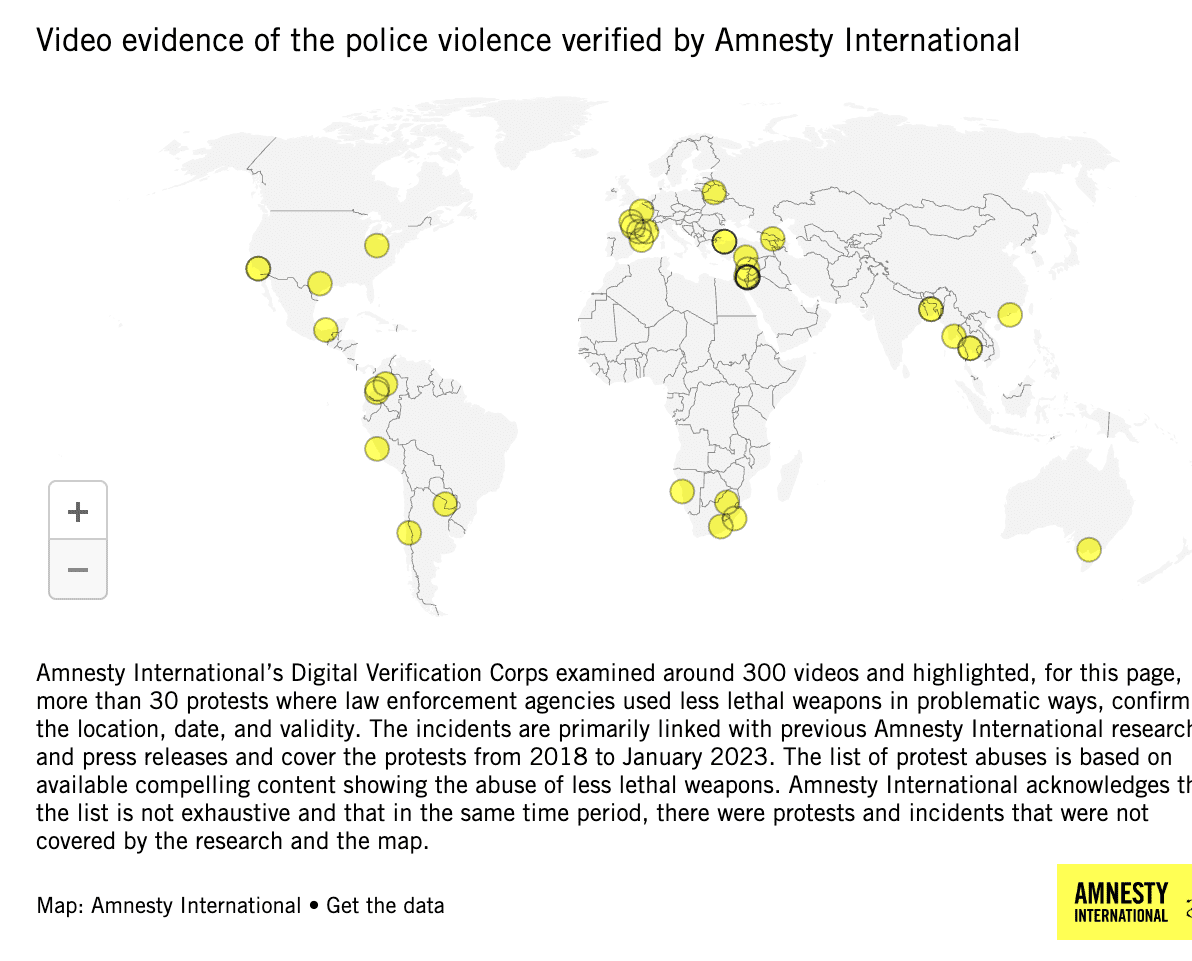

To investigate global abuse of the kinetic impact projectiles (KIPs) that we want regulated through the Torture-Free Trade Treaty, Evidence Lab partnered with the Law and Policy team to produce compelling research that combines traditional research methods with visual elements. The project also envisioned a critical campaigning element that included posts on multiple social media accounts, with coverage through traditional media outlets, petitions and advocacy meetings. Outputs were also to be communicated in four languages to reach wider global audiences.

As our project had an international scope, as well as a long timeline – looking into the abuse of these weapons in the last five years – we relied on the power of the DVC. They’re our network of student volunteers placed at six universities that collaborate with us to support our large-scale research. For this work, we ensured students had training in discovery, verification, ethics and resilience, as well as project focused sessions on right to life and weapons analysis. The training was followed by mentoring sessions held together with the faculty, staff, and student coordinators. During this semester-long project, DVC students verified more than 300 videos that included footage of possible police violence against the protesters. The videos were then analyzed by researchers and weapons analysts, who selected the final 75 incidents in 30 protests around the world that showcase problematic use of the less lethal weapons by law enforcement agencies.

The video evidence accompanied the research report My Eye Exploded that documented how security forces across the world are routinely misusing rubber and plastic bullets, and other law enforcement weapons, to violently suppress peaceful protests and cause horrific injuries and deaths. According to the report, the weapons have led to permanent disability in hundreds of cases and multiple deaths. The report also found that national guidance on the use of KIPs rarely meets international standards on the use of force, which state that their deployment be limited to situations of last resort when violent individuals pose an imminent threat of harm to persons. Given the grave human rights impacts of KIPs, strict national, regional and global regulation over their adoption and use, as well as their design and trade, is essential.