Not only has COVID-19 brought challenges to our health and our economy, it has also tested our universal system of human rights. Governments around the world have imposed measures restricting various rights, such as freedom of movement, to combat the spread of the virus, ranging from limits on group gatherings to strict nationwide lockdowns. Such emergency measures may be justified during the current public health crisis, provided that they meet the criteria of legality, necessity and proportionality established by international law and are enforced in a non-discriminatory manner. Unfortunately, Amnesty International has observed an increase in human rights violations by governments and law enforcement officials across the world, many of which have been visually documented and publicized on social media platforms.

Now, more than ever, rigorous verification is imperative.

Mitchell Paquette & Ariela Levy

With international and local travel restricted, conducting research into human rights concerns from the field is more challenging, lending increased importance to desk research and information gathered remotely through open sources. In this blogpost, we review the main types of violations that digital open source investigations (OSINT) have been able to reveal, including killings, the use of excessive force, humiliation, and opportunistic government overreach. Additionally, we outline some of the steps that Amnesty’s Crisis Evidence Lab has been using to monitor possible human rights violations during this crisis.

Types of Abuses

Cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment

Across Latin America, police have used humiliating and degrading tactics against people accused of breaking quarantine or other social distancing measures. We have seen multiple videos of forced group exercises and humiliation in several countries, including Venezuela and Dominican Republic, and inhumane treatment of individuals sleeping on the streets in Argentina and transgender people in Colombia. We have also seen detention used as a first, rather than last, resort, in the policing lockdowns.

Oftentimes, it is challenging to verify these videos as they may not show geographic context, particularly those filmed inside police stations where individuals may have been detained. In this case, we have analysed accents and details on police uniforms and equipment to help identify in what country the video originated. We’ve also used other indicators to ensure that the videos have been filmed since the COVID-19 crackdowns have started, asking ourselves, for instance, if people depicted in the videos are wearing masks, or if the video was posted after restrictive measures were first declared in the country of origin.

Excessive force

From the early stages of the response to the pandemic, security forces in various countries have used excessive force against those who disobeyed newly imposed restrictions. In France, videos surfaced of police resorting to aggression, trending with hashtags such as “#confinementotal” and “#ViolencesPolicieres.”

Security forces in India and Sierra Leone have beaten people with batons, and Kenyan police deployed tear gas on crowds at Likoni Ferry, Mombasa, potentially aggravating the risk of spreading the disease as people coughed and wiped their face and eyes to relieve irritation. In Nigeria, excessive use of force has been particularly grave, with reports of up to 18 people killed by security forces since the start of nationwide lockdowns.

Videos from Guajira, Venezuela have also emerged showing indications of use of force against Indigenous peoples during a protest for water, food, and medications.

However, not all of the open source videos of police violence that we have come across have proven to be COVID-19 related. A real feature of the social media landscape at this time has been recirculating older videos, taken out of context. If and when possible, it can be helpful to translate what is being said in the video in order to obtain as much context as possible surrounding the documented event.

Assaults on migrants and refugees

As countries around the world have closed their borders, challenges for migrants and refugees are mounting.

In Venezuela where returning refugees are being held in obligatory quarantine, Amnesty verified videos that surfaced of protesters inside an indoor stadium in Pueblo Nuevo, Táchira, where Venezuelans recently returned from Colombia were being held in alleged difficult conditions. Meanwhile, Venezuelans still living in Colombia face uncertainty regarding whether they are allowed to stay in the country.

Similarly, in El Salvador, thousands of people who broke mandatory quarantines have been placed in containment centres. Footage shows Salvadorians who recently returned to the country battling a rainstorm in one of these open-air containment centres.

At the Chile-Bolivia border, Bolivians faced a confrontation with the military after border closures limited their mobility. Footage from a camp just across the border in Pisiga, where recently repatriated Bolivians were being held in quarantine, provided early warning of poor living conditions and inadequate facilities.

Ongoing efforts by President Trump to limit immigration in the USA have increased the hardships many migrant families and asylum seekers face, which will only be aggravated by the administration’s recent decision to temporarily suspend immigration in an effort to combat the pandemic. Many see this move as a manipulation of the pandemic to promote xenophobia.

Failure of the system

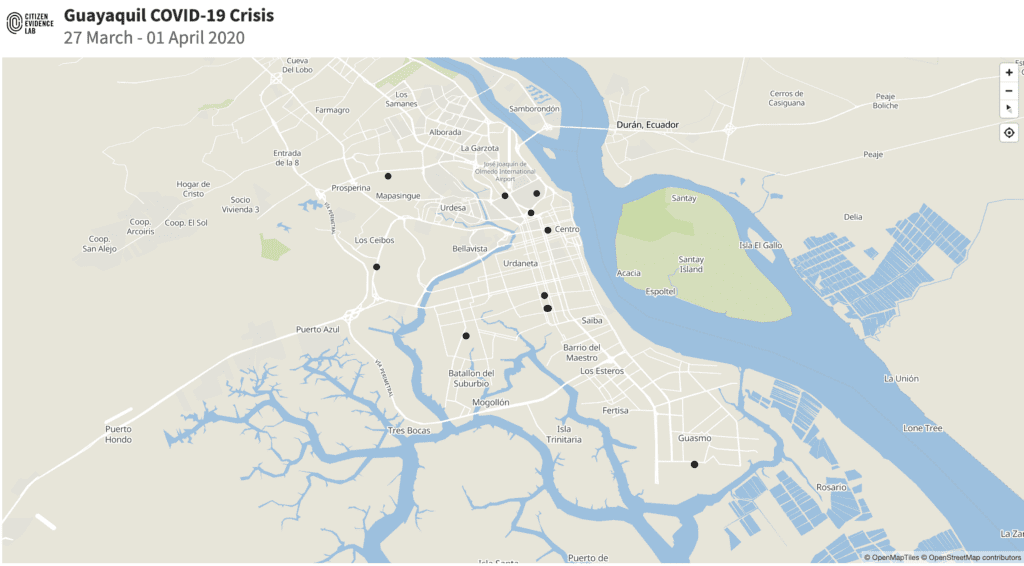

One of the places in Latin America worst hit by COVID-19 has been Guayaquil, Ecuador, where the state has struggled to uphold its human rights obligations in addressing the rapid spread of the virus, and its public health obligations to deal with the more than 1,900 bodies that accumulated in the first two weeks of April. Even before news outlets reported on the surging death toll, evidence of this grim reality was circulating on social media. Amnesty monitored the situation closely, verifying numerous videos of corpses left in streets or family homes, overwhelmed health facilities, long lines of people waiting to receive bursaries for the burials of relatives, and the preparation of emergency burial grounds. The audiovisual material shared by residents provided Amnesty with a clear and early indication as to the emerging crisis in Guayaquil and allowed us to map its widespread effects across the city. Since then, further data on the mortality rates in Guayas, Ecuador has become available, corroborating the increased death rate.

Arbitrary/excessive powers

In response to the global pandemic, numerous countries have adopted emergency laws or regulations that impose limitations on human rights and fundamental freedoms. While such laws may be compliant with human rights obligations–provided that they adhere to the above mentioned principles of legality, necessity and proportionality–there are concerns that some countries have capitalized on the pandemic to claim arbitrary and/or excessive powers. For example, the Hungarian parliament granted Viktor Orbán sweeping and broad-reaching emergency powers, allowing him effectively to rule by decree. While the decision was announced as a response to the pandemic, the move further erodes the already declining rule of law and respect for human rights in Hungary. As this crisis progresses, Amnesty intends to use the open source research methods outlined in this blog post to monitor whether emergency measures are being enforced in a discriminatory manner or otherwise misused, as well as to track whether such limitations on human rights continue to be enforced after the public health emergency has ended.

Social media monitoring

Finding relevant content can be particularly challenging when terms of interest, such as “COVID-19” and “coronavirus,” are trending hashtags worldwide. Developing the right search phrase is the first step to filtering out the noise to discover relevant content. Searching in the original language (as we detailed here) can be an important start. Boolean search terms will help further narrow or broaden your search (see this guide from First Draft News for more information).

For example, in our initial monitoring of security forces humiliating curfew breakers, we found content from Venezuela using the terms “policía,” and “abusivo,” as well as the hashtag “#QuedateEnCasa.” In India, the use of hashtags such as #coronajihad and #biojihad have been linked to the spread of anti-Muslim disinformation, while the hashtag #ChinaMustExplain has been used to draw attention to incidents of discrimination and harassment of Africans in China.

Also, searching the names of specific towns instead of a country helps further narrow down content. While results for “Ecuador” and “COVID-19” can seem unmanageably diverse, a search for “Guayaquil” and “COVID-19” helps limit what comes up. News outlets, both local and national, can provide hints for which towns are facing problems. As pieces of relevant content are discovered, keeping track of trending hashtags becomes really important, as do locations, terms and accounts of interest.

Geospatial monitoring

From mass movement of people, to the construction of new buildings, a lot can be detected through remote sensing data such as satellite imagery. In the Crisis Evidence Lab we regularly use these methods to track and verify human rights abuses. Looking for large groupings of new structures, or areas where people are being forced to gather – such as the Turkey/Greece border, or tents in the Darfur region of Sudan – can reveal problems that we might not otherwise be able to monitor. These tools have also been useful in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated challenges to immediate on-the-ground access that it presents. For example, when monitoring the crisis in Guayaquil, we used satellite imagery from early April to assist with corroborating video footage allegedly showing the construction of emergency burial sites. In other countries, satellite imagery also allowed us to monitor activity along border areas, providing indications of border closures, the build-up of security at checkpoints, and the establishment of temporary camps. We have also explored the potential for using remote sensing data to monitor other important sites, such as hospitals and prisons, to provide early warning of possible human rights concerns.

Ethical questions

While monitoring individual cases of abuse using open source investigation, one important question has been at the front of our mind: by highlighting these videos, are we risking the retraumatization of the individuals depicted in them? This has been particularly the case when looking at videos of alleged ritual humiliation by police, including towards women, transgender people, and other historically marginalized groups, for two main reasons. First, the content of these videos can be humiliating enough if they are circulated in small circles. An organization such as Amnesty International amplifying these videos then creates the risk of greater humiliation. This concern is further increased by the second point: many of these videos are filmed by the police, the perpetrators of these violations. The subjects of the videos did not give their consent to be filmed, nor did they have a choice. While it’s important for Amnesty to raise awareness about such human rights violations, and hold the state to account for them, it’s also important we do so ethically, without retraumatizing the victims today, or further down the road.

The ideal solution to this problem is obtaining informed consent for the use of the video or photo from the subject of the video. If this is not possible, next steps would be to only report an event, but not share or amplify the content, editing elements of the video to avoid portraying the person depicted in the content, or blurring features to mask the person’s identity. Whatever the choice taken, a due diligence exercise needs to be conducted that balances the potential harm to the person or people depicted in the content against the benefits of showing a video or photograph.

Tackling the COVID-19 infodemic

As with all aspects of responding to the COVID-19 pandemic, our use of OSINT has been a rapid learning experience. Amidst the constant media coverage of the public health crisis, there has also been a flood of mis- and disinformation related to COVID-19. In this context, which some experts are calling a parallel “infodemic,” the Crisis Evidence Lab has encountered numerous posts spreading false information on social media, including the resurfacing of old videos of police violence purporting to show abuses of power under COVID-related lockdowns. Falling victim to these false accounts can happen to anybody, as just earlier this month we examined a shocking video from Brazil in which security forces fired less-lethal ammunition on a public beach. Upon initial verification we believed the police were enforcing quarantine regulation, but a revision of the video in question revealed the event occurred last year and was unrelated to COVID-19. Now, more than ever, rigorous verification is imperative.

While open source information has been a valuable resource for monitoring and investigating human rights violations carried out in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the widespread confusion and uncertainty during this global health crisis has also exacerbated the challenges of conducting OSINT research. Coupled with the increased challenges to conducting field research, the Evidence Lab has had to be creative in our approach, using all of the tools at our disposal to carry out effective, accurate research.