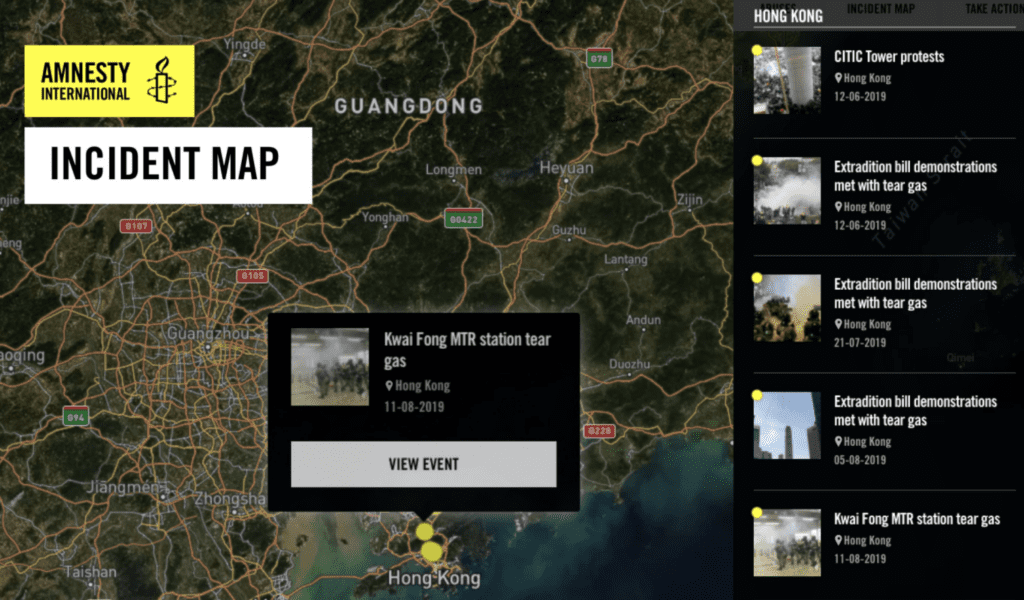

Tear Gas: An Investigation is the result of 18 months of research, documentation and analysis by Amnesty International. The multimedia site looks into what tear gas is, how it is used and documents scores of cases of its misuse by security forces worldwide, often resulting in severe injuries or death. As most protests today are filmed and shared on social media by participants or observers, we were able to collate hundreds of videos and – using an interactive map – highlight some of the worst instances of tear gas misuse in 22 countries and territories on five continents.

DVC-LED ANALYSIS

Early last year, our Digital Verification Corps (DVC) started discovery, verification and analysis of 500 videos, allowing the Evidence Lab to consolidate the analysis and build the platform. With so many instances of alleged tear gas misuse to go through from the past three years alone, this was a DVC project on which every one of our current partners worked. It was a truly global undertaking.

Here we explore the workflow that the DVC goes through in its open source analysis, and look at how we source, archive, and analyze open source content to document human rights abuses.

- Sourcing Content

Amnesty’s open source investigation workflow begins with sourcing images or videos that show potential human rights violations. In some instances, we receive content directly from our regional researchers through their networks of contacts, or other sources on the ground during a developing crisis. This might include content that sources have recorded or that they received through closed networks. For Tear Gas: An Investigation, the DVC engaged in a comprehensive discovery process to identify and collect open source material relevant to the project from a variety of digital platforms. Focusing on the major social media platforms including Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, DVC volunteers are trained to carry out exhaustive searches using advanced search techniques, identifying keywords in all relevant languages, and monitoring events in real time. As situations on the ground evolve or research parameters change, the DVC continues to monitor for additional audiovisual material. This combination of both received and discovered content forms the foundation of each open source investigation and is fundamental to the success of the research.

- Preservation

The next step in the DVC’s open source investigations workflow is to preserve all content that we intend to analyze and possibly use as evidence in future research outputs. This is essential when working with open source content as it may be removed by the uploader or deleted by the social media companies. Amnesty’s process for preservation is twofold: first, to download the audiovisual content collected in the previous stage of the workflow using the tool youtube-dl. Second, to upload the preserved media file to Amnesty’s secure archive where it is stored and catalogued for future analysis and referencing. As a general guideline, when Amnesty preserves content we consider whether a particular preservation methodology is understandable (i.e. can be easily understood and replicated by other researchers and DVC volunteers), whether it is authentic, and whether it is preserved for the intended use of documenting human rights abuses.

- Documentation

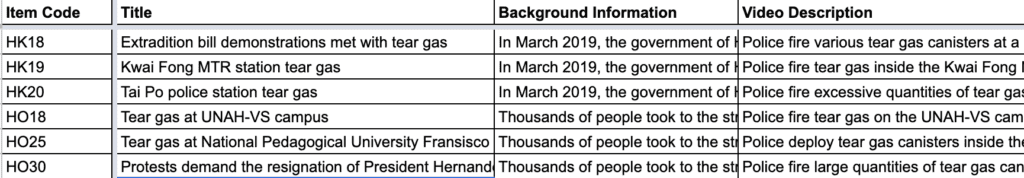

Tear Gas: An Investigation was a data-heavy project, with hundreds of videos discovered and preserved. In order to properly analyze these individual pieces of content, having a robust system for storing, structuring and retrieving data was critical. All the content was collected in our collaborative platform Truly Media – with each country separated into separate collections or folders. When verification was complete, we then exported all the data as a .csv file, and created shared spreadsheets for the analysis stage. At this point, each individual piece of content was given a code as it was entered into the system, which was critical as the project progressed and we started building the platform (in this case, it was the two-letter NATO country code followed by two numbers (so, e.g., US23)).

Getting the data structure right is very important, and failure to do so at this stage will cost a project when it approaches completion and publication.

- Verification

Before any content sourced during an open source investigation can be used as evidence, it is verified for its authenticity and accuracy. The verification methodology includes analysis of: a) the origin of the content; b) the source; c) the time/date when the event depicted occurred; d) the location where the content was captured; as well as e) identifying any corroborating evidence that supports what is shown in the content. As indicated by the workflow graphic above, oftentimes while verifying material we discover additional content related to the investigation. In this event, we begin another cycle of preservation, documentation, and further verification of the new content.

i) Origin

The first step that Amnesty’s open source researchers take when verifying an image or video is to evaluate whether what they are viewing is original content and if not, to establish when the content first appeared online. Given the nature of digital platforms and the ease with which content can be shared, downloaded and recirculated, there is always the possibility that a piece of content may be falsely linked and distributed in connection with an event that may have nothing to do with the original.

One of the most effective means of determining this is to conduct a reverse image search on a photo or stills from a video. Doing so allows researchers to search online databases such as Google, Bing, Yandex, and Tineye for visually similar or identical images. If the content has appeared online before the date of the event in question, this would suggest that the photo or video is being shared out of context or used in a misleading manner.

ii) Source

Verifying the source is an important aspect of establishing the credibility of a piece of content. This could include both the primary source (i.e. the person who captured it) and the person who shared it either directly or online.

In instances where content is received directly from an individual or organization, this process involves evaluating the degree to which the source is trusted and credible based on whether they are a known source within Amnesty or other peer organizations, the accuracy of their past reporting, their proximity to the alleged location of the event, and how they gained access to the content. For open source content such as that shared on social media platforms, this process of source vetting is more involved given that users can provide minimal or inaccurate information about themselves, which may be difficult to independently verify.

Some platforms provide visual indicators of users that they deem ‘verified’ based on a range of criteria. However, researchers also look for other indicators as to the identity of the source such as their stated location on the platform, whether their shared content is consistent with this location, whether they have an online footprint linking the same user across multiple platforms and online profiles, and whether any contact information for them is available. Some of the tools that we use in this stage include Twitonomy, which can assist in identifying automated or ‘bot’ accounts on Twitter, and reverse image search to find other instances of the same profile picture online.

iii) Time/Date

Establishing the date and time when a photo or video was captured is crucial to verifying whether a piece of evidence is likely connected to a particular event. In some cases, footage of an event might be uploaded to social media immediately after it is recorded. In others, content might surface days, weeks, or even years after it was originally captured. For this reason, determining the precise date/time when a video was recorded is an important part of Amnesty’s verification methodology. For content that is shared directly with Amnesty’s researchers, one resource that we may have in this regard is metadata (or ‘Exif data’) which is stored within the media file and contains information such as the the type of device it was captured on, the time and date recorded by the device at the time of capture, and possibly even the coordinates if the device’s GPS was active.

Tools like InVid’s metadata viewer or Jeffrey’s Metadata viewer can be used to access this data. Unfortunately, nearly all social media platforms remove metadata from all media files uploaded to the platform, so this information is often not available for content discovered online. In such cases, Amnesty begins by first looking at the timestamp of the content when it was uploaded. While this does not necessarily reflect when an image was captured, it may give an indication of this (InVid upload times in UTC).

A more precise method for determining capture time/date is through chronolocation of an image or video. This could be done through the use of historical satellite imagery to determine at which point in time a major change in the features of a location, such as the construction of a new building or the burning of a village, was first captured by satellite. Other tools like SunCalc or Wolfram Alpha may be used to analyze the position of the sun or the weather at a particular day/time in a specific location, which may also help verify the time and date on which an image or video was captured. Finally, we will look for corroborating evidence such as news reports that specify the time of the incident under investigation or look at the upload times of other content that appears to be from the same event.

iv) Location

Each piece of content received or discovered is analyzed to verify the location where it was captured. It is commonplace when working with open source material to find content captured in one conflict zone transposed to another or for users to make false allegations about the location where an event took place. When using such materials as evidence of human rights violations, verifying the location where an incident took place is essential to the strength of that research. Some content is geotagged on social media platforms, however, the accuracy of these tags cannot be relied upon and independent verification is always necessary.

To geolocate visual media, Amnesty researchers look for unique geographical features, buildings, street signs, shopfronts, or other reference points that can be detected on satellite imagery or other mapping tools such as Google Maps, Google Earth, Bing Maps, OpenStreetMap, and Wikimapia. In some cases, there may be telephone numbers or business names that can be entered into search engines and located by their advertised street address.

Uploaders of content often give explicit indications as to the location of the event in the text of their posts which can provide an initial reference point to begin geolocation. In other cases, such information might be inferred from the stated location of the account that shared the content or from the location noted in previous posts from the same user. Other details such as the language and dialect spoken by individuals present in a video or the clothing they are wearing may be useful in determining the location where the footage or image was captured.

v) Corroborating Evidence/Testimony

In addition to corroborating information regarding the date, time, and location of a piece of content by cross referencing it against other media reports from the same incident, Amnesty will also corroborate open source evidence by comparing it to witness testimony collected by researchers in the field. This is useful not only in confirming key details about where and when an incident took place from those who were present but also in developing a more detailed account of what took place during the event and the main actors involved. When possible, Amnesty will also analyze other aspects of the audiovisual content such as the weapons or military equipment used and the uniforms of those involved. These details may be unique to certain state forces operating in an area or be linked to a particular armed group and can help establish likely perpetrators.

- Evaluation

After open source content has been verified, the Evidence Lab must then evaluate if and how we use the material as evidence in support of Amnesty’s research findings. In the case of Tear Gas, the analysis also included asking if there was enough material to warrant building a whole platform. Done honestly and objectively, this is a vital step for both maintaining the highest possible standard of research as well as effectively integrating open source information alongside more traditional methodologies for human rights documentation.

Among the factors we consider is whether and how clearly a human rights violation is depicted in the verified media, whether the content is compelling, and whether it can be corroborated by other types of evidence gathered, such as eyewitness testimony and remote sensing. We will then consider what conclusions can be definitively drawn based on the verified footage alone and compare this for consistency with reports received through Amnesty’s field researchers and other NGOs and news outlets. For Tear Gas, in many instances we were able to also check our conclusions against Amnesty’s former research findings, and have integrated relevant press releases into the platform per event.

This workflow and methodology is integral to the building of Tear Gas, just as it is integral to ensuring the accuracy of many of Amnesty’s open source investigations. In some cases it provides an additional pillar of evidence to Amnesty’s work documenting and exposing human rights abuses, as well as making it possible to conduct investigations at scale. We continue to refine this workflow informed by past investigations and new developments, and explore how open source research can best complement other research methodologies. In the case of Tear Gas, we are able to use open source information to contradict the claim that tear gas is a ‘safe’ way to disperse violent crowds, and show that police forces are misusing it on a massive scale. Without the DVC and this workflow, that undertaking would have been much harder, if not insurmountable.