This article discusses traumatic events including sexual assault.

Documenting human rights abuses while working as an open source researcher often places you at risk of vicarious trauma. However, there are actions you can take to mitigate the risks and safeguard your wellbeing.

Amnesty International is committed to supporting the mental health and wellbeing of all of its staff and volunteers. As psychologists, we were invited by FD Consultants to participate in the Digital Verification Corps (DVC) summit in Mexico City to provide vicarious trauma training. The DVC is a network of students from six global universities who support Amnesty International’s human rights research. Below, we will outline key lessons learned from these workshops, that can hopefully assist the wider open source community when working with traumatic material.

What is trauma?

We cannot predict what will be traumatic for one person, and not for another, only knowing details about the traumatic event itself.

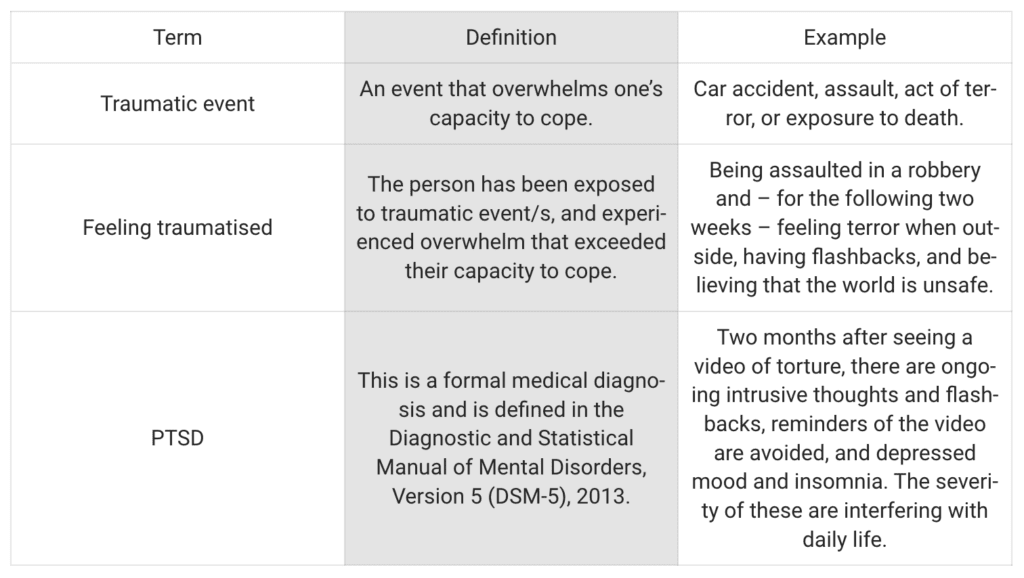

First, it is important to have an understanding of what trauma is. A traumatic event, feeling traumatised, and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) are terms and concepts that are often used interchangeably, so let’s start with some definitions.

How we respond to each potentially traumatic event is influenced by three main groups of factors. They are:

- Factors related to the incident. For example: severity, threat to life, unpredictability, duration, feelings of horror, single versus recurring, etc.

- Factors related to the individual. For example: history of trauma, mental health vulnerability, relatability, overall wellbeing, age, gender, cultural beliefs, family history, economic status, access to resources, coping abilities, capacity at the time, and previous incidents within a short time frame.

- Factors related to the social response. For example: support after the incident/exposure, blaming, safety, buffering factors.

Feeling traumatised and/or the development of PTSD involves a complex interplay of factors linked to the incident, individual, and social response. Thus, we cannot predict what will be traumatic for one person, and not for another, only knowing details about the traumatic event itself.

For example, consider someone who was sexually assaulted. The social response could be that investigators believed the person’s story, they were provided with services, and the perpetrator brought to justice. In another instance, the person was disbelieved, blamed, and placed in high-risk situations with the perpetrator. The impact of the trauma, following the initial event, is influenced by these external ‘social response’ factors, which can differ in every situation.

Similarly, consider someone who sees photos of a murder. They walk into a dedicated workspace and view the photos for a specific research purpose. After seeing the photos, they speak to a colleague who provides empathy and validation. Later, they physically leave work and shift to self-care and being with friends. Compare this to someone being on a night out with friends and receiving a WhatsApp message that unexpectedly has multiple photos of the murder. They feel distressed, but do not feel it’s appropriate to talk to friends about what they’ve seen. They become quiet and withdrawn and are distracted by thoughts of the photos. By night-time, the images continue to run through their head, and they cannot fall asleep. They get up to have a glass of wine.

Consider that in both cases the person was exposed to the same material. However, due to the differing circumstances around the exposure, the level of impact can also be different. If you multiply this experience over many exposures each day, week, month, or year, the difference in the cumulative impact becomes even greater.

What is vicarious trauma?

Vicarious trauma is sometimes called secondary trauma. It refers to indirect exposure to someone else’s trauma resulting from viewing graphic imagery, supporting a trauma survivor, or hearing accounts of traumatic experiences. It can be just as distressing as primary trauma, i.e. trauma that occurs directly to you. PTSD may be induced by vicarious trauma. Therefore, if you are exposed to traumatic material, it is essential that careful thought and planning goes into modifying the variables that are under your control in order to minimise the impacts of vicarious trauma.

It refers to indirect exposure to someone else’s trauma resulting from viewing graphic imagery, supporting a trauma survivor, or hearing accounts of traumatic experiences

Caring for yourself

Preparation

- Ensure all traumatic material is labelled as such before sharing it with others. Labels allow someone to be prepared to only view the material when their circumstances are appropriate.

- Reflect on what is most distressing for you. This is individual, and often (but not always) links to what is personal to us. For example, a new mother with a two-year-old daughter may be much more impacted by a video of a two-year-old girl than someone else. Where possible, minimise exposure to videos that hold a high level of personal impact for you.

- Before starting, have your research question in mind.

- Have a designated space for viewing traumatic material. Keep it out of your bedroom.

- Turn off the sound while viewing videos when possible.

- Create an individual care plan. Start with identifying how you are impacted by trauma exposure, and think of a strategy to intervene. For example:

- My heart rate increases = 10 minutes of deep breathing.

- Rumination (excessive and repetitive thoughts) = journaling for 15 minutes to process my thoughts, and then engaging in another activity.

- Telling myself I’m not doing enough = actively challenging these thoughts and replacing them with what I would say to a friend or colleague who was thinking this way.

Response

- Create space to ask yourself how you’re doing. If you’re feeling overwhelmed by watching something, then take a break. Ask yourself, “Do I feel I can rewatch this material right now?” If the answer is no, then respect that feeling and take a break from the material. You can ask yourself again later.

- Push yourself to connect. In times of distress, many people withdraw or disconnect. However, we gain benefits from connecting with others.

- If the feelings of distress still linger, reach out to someone to debrief. Tell them what you saw (details aren’t necessary, just a ‘headline’ description is enough), what you felt emotionally, what you thought about it, and what is still ‘sitting’ with you. Then make a plan for taking care of yourself.

- If you feel unsettled, engage in relaxation or exercise to help regulate your nervous system. Try to avoid engaging in avoidance-based behaviours, such as drinking excessive alcohol, to feel calmer.

Your greatest resources are other staff and volunteers at Amnesty International, or your peers and colleagues at other organisations. Stay connected, support each other, share ideas, and try to be open and authentic about your experiences.