This blog post is also available in French here.

In this blog, we’ll discuss the challenges of verifying video evidence from the recent repression of protests in Dakar, and detail how the Evidence Lab was able to geolocate a potential extrajudicial execution by the Senegalese police.

Dakar rises: potential extrajudicial executions in the capital

The arrest of Senegalese opposition politician Ousmane Sonko, on 01 June 2023, triggered a wave of spontaneous protests in the capital city Dakar, which lasted for approximately a week. These protests were met with an excessive use of force by the Senegalese police, and limits to freedom of expression and information as already denounced by Amnesty International. Since then, based on Amnesty International’s own data, at least 23 people have been killed and over 390 injured, according to the Senegalese Red Cross.

Fact-checkers and open-source analysts have already use footage available from these events to question the Senegalese government’s policing strategies, and in particular its alleged use of armed non-uniformed operatives (locally known as ‘nervis’), who have been seen closely collaborating with the Senegalese police on several videos, equipped with both less-lethal and lethal weapons.

The Crisis Evidence Lab, in close collaboration with Amnesty International’s regional office in Dakar, is currently combing through available footage to ensure that crimes and potential extrajudicial executions caught on camera in Dakar will not remain unpunished.

But verifying video evidence in a city like Dakar remains nonetheless difficult, given the frequently changing landscape (making comparisons with photos archived in Google Street View difficult for instance), the relatively narrow streets and lack of geolocation clues (signposts, street signs, shops etc). In this context, close collaboration with Amnesty researchers based in the regional office has been key to making progress narrowing down the locations where videos have been captured.

One case that caught the eye of international media and created a stir in Senegal is the death of Abdoulaye Camara, a producer and hip-hop artist known as ‘Baba Kana’, who was shot to death by the police on 3 June. As a source close to Abdoulaye Camara told Amnesty International: ‘This Saturday, June 3, Abdoulaye had gone to visit one of his friends in Ouagou Niayes. On his way back to Niarry Tally, he encountered a crowd of protesters and police and was hit by bullets. In videos that have circulated widely on social networks, we see that he was then beaten by the police officers of the HLM police station while he was on the ground and dragged into the street. Throughout the day on Sunday, we went back and forth to the HLM and Dieuppeul police stations to find out if he was there, but it was the Dieuppeul fire brigade who told us that a body supposedly ‘picked up in the street’ had indeed been deposited there by the police on Saturday evening. Finally, on Monday, we found his body at the morgue of Dalal Jamm hospital in Guediawaye.”

Unsuccessful attempts at geolocating Camara’s death

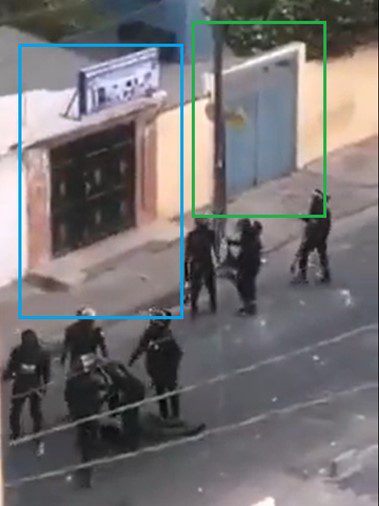

On various videos circulating on social media and analyzed by the Evidence Lab, Abdoulaye Camara is seen being hit and dragged on the floor by police officers in at least two distinct videos (stills from videos 1 and 2 below), taken from balconies across the street. In a third video (still number 3 below), taken from the end of the street at ground level, shows a large number of police officers – but Abdoulaye Camara cannot be seen.

Geolocating video content is an important step of our verification work, designed to ensure the reliability of the evidence that we use in our publications. Identifying the district of Dakar where these events took place was fairly straight-forward, as witnesses had the simple idea of marking footage with the name of the neighborhood where events took place: Ouagou Niayes in HLM, within the commune of Biscuiterie. However, none of the videos provided actionable clues in order to precisely geolocate them.

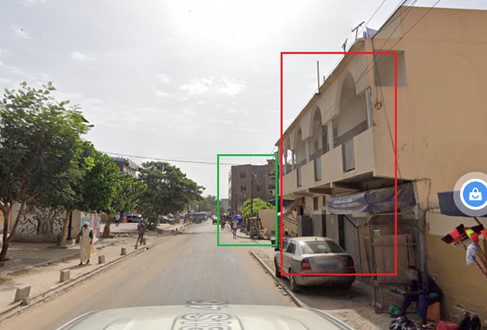

Several attempts were made in order to spot distinctive features, such as the bright red shop that can be seen on the left side of still n°1, the blue and white shop sign that appear in both video n°1 and 2, or the distinctive white and red concrete blocks marking the sidewalk on video n°3. Yet all these attempts proved unhelpful; for example, because shop signs were unreadable and the shops were not referenced on any web-based maps.

The Sufi lead

Towards the end of video n°3, however, we could make out an odd-looking white mural from which bystanders are observing the police violence. On this mural hangs a plaque, with only few readable words given the quality of the footage. However, checking the original Tiktok video revealed slightly better definition and allowed the chance to decipher a few more words.

While the Twitter version only allows to decipher the first word, “place”, the Tiktok video reads, “Place Serigne Babacar […] Khalife Général […]”. Despite the fact that “Serigne Babacar” is an extremely common name in Senegal, only one of them seem to have been a Khalife Général: Serigne Babacar Sy Mansour, the general Khalif of the Tijaniyyah tariqa, a Sufi order widespread in West Africa.

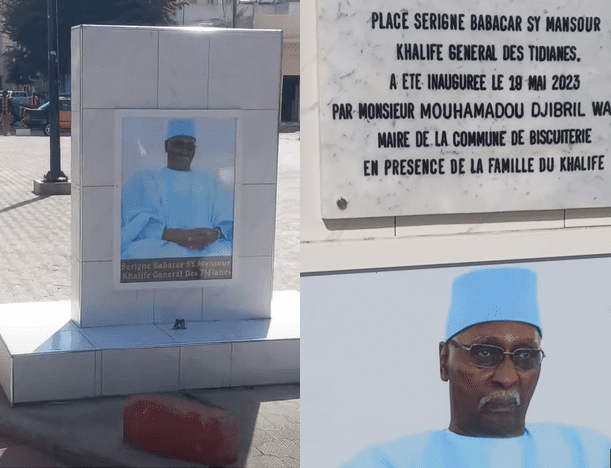

The Serigne Babacar Sy Mansour square is however nowhere to be found in online maps, even through targeted searches in HLM and Ouagou Niayes. One Youtube video, posted only two weeks before the protests started, does show the freshly built tribute with Serigne Babacar Sy Mansour’s portrait, as well as, on the opposite side, the plaque seen in video n°3.

This video allowed us to make targeted Google searches for content related to Serigne Babacar Sy Mansour around the unveiling date of the mural, 19 May 2023, as well as to design search queries using key words from the mural, and therefore more likely to have been used in the coverage of the unveiling. It also offered the chance to match the video of the mural with various elements spotted in video n°3, including the red concrete block that could be seen on the left-side picture above.

Targeted Google searches using search operators and keywords from the plaque (such as “inauguration”, “Mouhamadou Djibril Wade”, etc) led to the official Facebook page of the Biscuiterie commune. Searching for content posted around the second half of May 2023 quickly led to another video of the inauguration, whose caption, in French, referred to the former name of what is now Serigne Babacar Sy Mansour square: ‘Place Lemgui’.

Lemgui square is referenced in Google Maps and appears on Google Street View, which allowed the Evidence Lab to very quickly spot the street seen in video n°3, and also spot the exact location where Aboulaye Camara is seen injured by police officers on the 3rd of June 2023.

It’s the smallest details: lessons learned for future geolocations

In theory, with enough time and resources, all social media content can be geolocated. Tracking down violators and collecting reliable evidence through digital content analysis nonetheless remain extremely challenging in some contexts. Dakar, with its often-changing landscape, typically isn’t an easy target for open-source analysts. This case study however shows how methodical analysis of visual clues, and cycles of trial and error, allow us to slowly make progress to pinpoint specific locations where human rights violations may have happened.

This time-consuming process is a key prerequisite to ensure that Amnesty’s analysis is built on reliable evidence, that investigators can draw on accurate facts and analysis, and that impunity does not reign supreme. The Evidence Lab, and Amnesty International’s Regional Office, is continuing its investigations on the brutal repression of the protests that rocked Dakar, a city that also constitutes the backdrop of many of Baba Kana’s videoclips.