The report ‘Nowhere is safe for us’ documents attacks on schools and hospitals in towns and villages in Idlib, western Aleppo, and north-western Hama governorates in Syria from December 2019 to March 2020. These attacks, carried out by Syrian and Russian government forces, entailed a myriad of serious violations of international humanitarian law.

It takes a team effort and collaboration between different experts to collate, corroborate and confirm evidence of war crimes. This blogpost takes us through the steps that allow us to integrate different forms of evidence into the research and use new methodologies for the first time.

The report documents 18 cases of attacks on schools and medical facilities. Documenting each of these requires a variety of research techniques. Here, we focus on one attack: on al-Shami hospital in Ariha, a town in central Idlib, between 10.30pm and 11pm on 29 January 2020. The hospital is on a “deconfliction” list the UN previously shared with Russian, Turkish and US-led Coalition forces in Syria to highlight which sites must not be attacked. By bringing together different research methodologies we were able to conclude that Russian government forces launched a series of three air strikes targeting the hospital and striking residential buildings in the immediate vicinity.

Never omit the interviews, but corroboration is key

The research is based primarily on interviews that Amnesty researchers conducted with witnesses. In the case of al-Shami hospital, we were able to speak to three people who were at the hospital at the time of the strikes, including a doctor who told us that, during the attack: “I felt so helpless. My friend and colleague dying, children and women screaming outside … We were all paralysed.” He told us that it took the civil defence two days to remove the bodies from underneath the rubble of one of the flattened buildings in Ariha.

The role of the Evidence Lab here is to corroborate such interviews. This means checking that the open source information and any other data that we can find matches up to the interviews, to check whether there are discrepancies between the information on the ground, videos posted to the internet, satellite imagery of the site of the attack, and other separate on-the-ground witnesses. In this case, corroborating the last of these deployed a new methodology for us: combing a collection of flight-spotter observations in Syria.

Using the Digital Verification Corps to source and verify videos

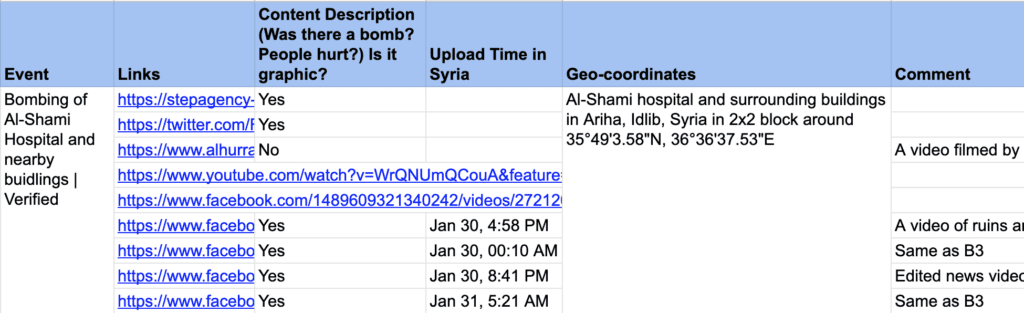

As a first step, we engaged the Digital Verification Corps, Amnesty‘s global network of student volunteers whom we have trained in digital verification techniques. In this instance, we received help from a group of five experienced volunteers from one of our partner organizations – the Human Rights Center at University of California, Berkeley. The team at Berkeley took a list of schools and hospitals that our interviews told us had been attacked and when, and conducted online inquiries to discover content that appeared relevant to this attack. They sourced videos and photographs posted online – in particular on Facebook and Twitter.

One challenge with the air strikes on al-Shami hospital was that they happened at night. Because it was not possible to use chronolocation techniques such as shadow analysis, it was important to use reverse image searches to ensure that content found online by the DVC was not from a previous event, and to confirm when it was uploaded to the internet in local time. A range of content showed the immediate aftermath of the strike, rescue efforts the following morning, and, finally, the clean-up. One of the first videos found, relating to the immediate aftermath of the air strike, was uploaded to the internet at 00:10 local time on 30 January, corresponding to soon after the eyewitness testimony of when the event happened. A check showed that this video had not appeared online before this date.

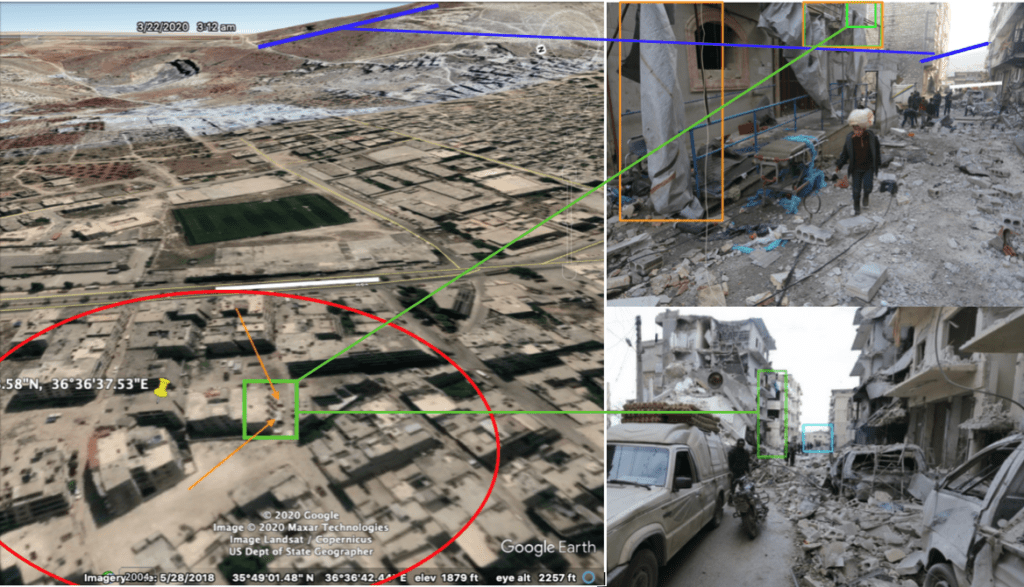

When the team had collated the videos that appeared to be of the strike in question, the next job was to verify their location. This required matching elements of the videos to the geographical features of satellite imagery – one of the most important parts of verification. To use this evidence, we had to know the timeframe was right, as was the location the videos were filmed in.

Satellite imagery to confirm time and place

With the hospital geolocated (using the DVC’s analysis of open-source video and photos), the next step was to turn to satellite imagery to verify if there was evidence of damage around al-Shami hospital. We sourced different types of satellite imagery. First, high-resolution satellite imagery was used to visually confirm and align ground photos of the damage in the area. Comparing images from 19 December 2019 and 3 February 2020 we could see the extent of the damage in the densely built area.

Second, we needed to confirm, as closely as possible, when the strike happened. Testimonies said the attack happened on 29 January 2020, which the verified videos confirmed. We were able to also use other sources to narrow down the timeframe in which the damage was visible in satellite imagery. Planet 3-metre satellite imagery was able to show change in the area between 27 January and 2 February 2020, increasing our confidence that we had the correct time and place of events.

Flight spotters for final verification

On this project we deployed a completely novel methodology. For the first time in our work on the Syrian conflict, we obtained a compilation of several thousand flight observations from individuals on the ground near Idlib. Only two government’s militaries are conducting air strikes around Idlib and Aleppo—the air forces of Syria and Russia—and after years of attacks, these flight spotters are experienced in distinguishing older aircraft – such as Syrian YAK-130s and Su-22s – from new Russian models, like Su-30s and Su-35s. When documenting an aircraft, they note its location, the exact time and date, the type of aircraft, and the general direction it is flying. With dates and strike locations at hand, not only were we able to identify the aircraft that conducted attacks for events in the report, but sometimes also track aircraft taking off from military airports, moving to the strike location, and then returning to base.

In this case, the strike on al-Shami hospital occurred at night. This itself is a big clue as to who was responsible, as night attacks are almost exclusively conducted by the Russians in this theatre of war. Flying and dropping munitions using night vision goggles is a difficult task requiring sophisticated equipment and significant training, and only a handful of the world’s air forces can do it accurately. In this case, the spotters had documented multiple sightings of Russian, and only Russian, aircraft in the area of the strike, between 10:22pm and 11:10pm on 29 January 2020, corresponding to the time of the bombing.

The key to all of this research is corroboration through collaboration. By bringing together different elements of research, Amnesty was able to build a body of evidence to show that, in the case of al-Shami Hospital, the Russian air force had violated international humanitarian law. The strike was part of a pattern of support for the Syrian forces’ crimes against humanity against the civilian population.

Civilians in north-west Syria – almost a million of whom were displaced by the latest offensive – continue to suffer intolerable living conditions amid harsh weather and shortages of food, clean water and medical aid.

On 10 July, UN Security Council Resolution 2504, which authorizes cross-border aid into north-west Syria, expires. The Syrian government and its allies are seeking to end this arrangement and replace it with aid channelled through Damascus. UN officials have already called Idlib a humanitarian “horror story.” The horror will only get worse unless the UN Security Council renews this cross-border aid mechanism.