Translation affects who can access our published work and who – through the decision to work in certain languages and not others – is included in the research. Yet, the decision to translate and how we handle translation rarely features in project methodologies and, unlike other tools or technologies, its impact can be hard to measure.

The Crisis Evidence Lab teamed up with Amnesty’s Language Resource Centre (LRC) to document how we work together and what makes a successful translation for both the investigator or researcher and the translator. The LRC works across the movement to enhance diversity, inclusion, and human rights impact. It is made up of a multilocation, multicultural, and multilingual team and comprises two main functional areas: translation and interpretation.

Why we translate

Central to our work and informing the decisions we make, are the people closest to and affected by human rights violations. These people become experts, sources, interviewees, and fixers in the production of the research. However, by the end of an investigation, resources are often scarce and there can be pressure to translate only into the languages that are most strategic for advocacy and campaigning purposes. In some cases, to do this excludes our collaborators as well as the people we are speaking on behalf of, such as survivors. For this reason, why and how we translate cannot be separated from questions of access and inclusivity. Put differently, translation is a vehicle for greater local impact and relevance.

Internally, English is the operational language of the Crisis Response Programme (CRP) and its Evidence Lab, but many of our colleagues and collaborators speak other languages. It is also true that most of our investigations focus on groups or regions that are not anglophone. Translation and interpretation can be necessary at any stage of an investigation from the identification, preservation, and analysis of research materials to the report writing and communication of findings. It affects international advocacy, public campaigns, and partnership building with local organizations

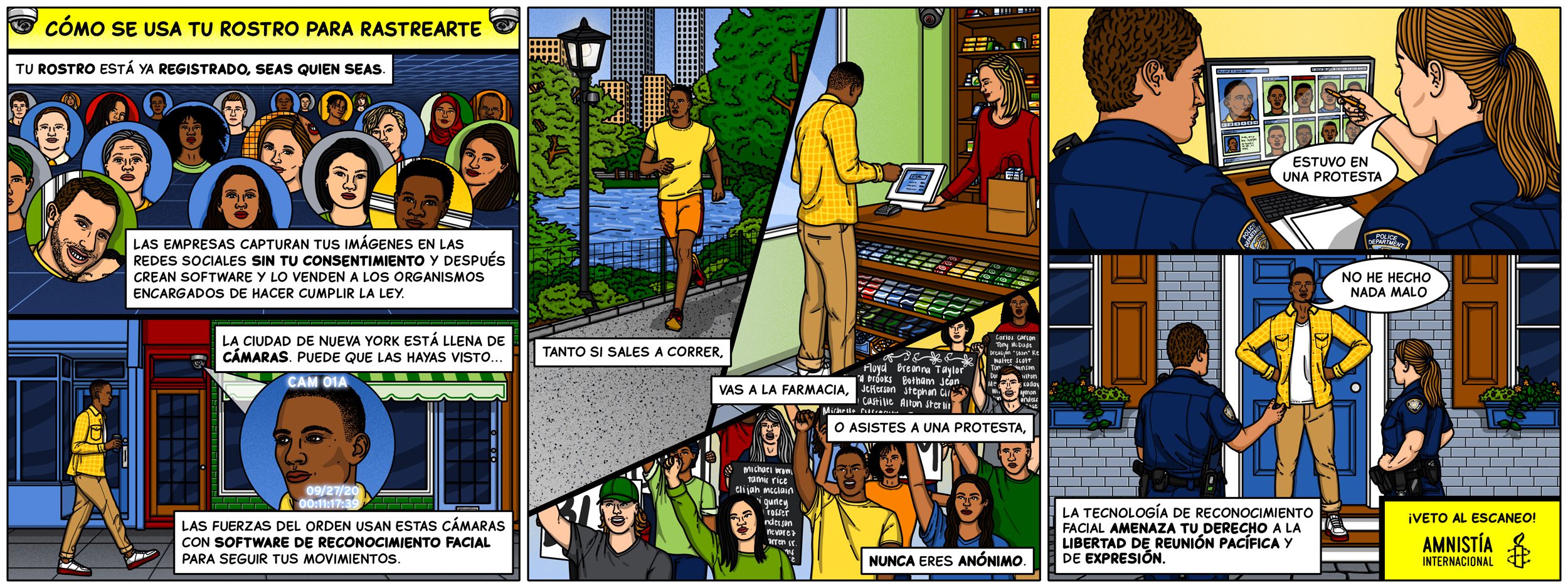

Last year, the CRP, Evidence Lab, and LRC collaborated to translate online resources, maps, and press releases in Arabic, Spanish, Farsi, Portuguese, Somali, and Hausa, amongst other formats and languages.

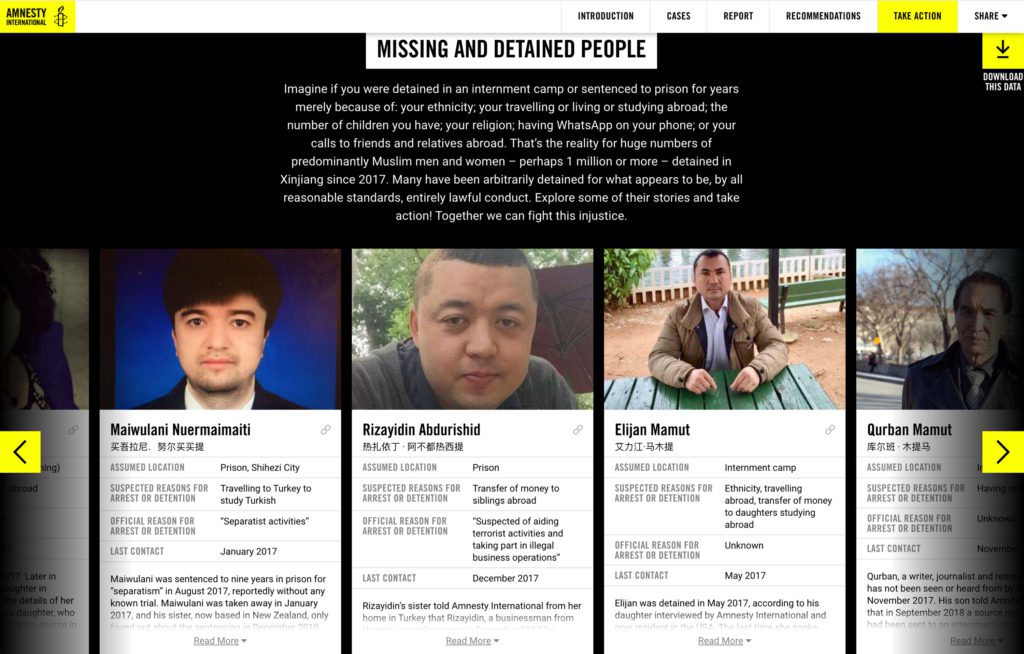

This year the key findings of a report on the repression of Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and other predominantly Muslim ethnic groups in Xinjiang were translated into 12 languages (Arabic, Bahasa Indonesian, French, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Russian, Simplified Chinese, Spanish, Tajik, Turkish, Uyghur, and Uzbek). These translations were distributed by Amnesty and our local partners in countries where many of the report’s interviewees, fixers, and interpreters were based. Online and outside Europe, Russian speakers, most located in Kazakhstan, were the largest language group to access the website, therefore underlining the importance of translation.

Technical terms explained

Just like any other specialism, translation has its own technical language. Below is a list of key terms used in the second half of this post.

| Source language | A language that is to be translated into another language. |

| Target language | A language into which another language is to be translated. |

| Localization | Translation is the process of rendering your text from one language into another so that the meaning is equivalent, while localization is a more comprehensive process that transforms the entire content or digital product from one language to another. It addresses cultural and non-textual components as well as linguistic issues, which can sometimes lead to some technical challenges, such flipping user interfaces from left-to-right to right-to-left. |

| Term base | Translation term base (short for terminology database) is a database containing approved terminology paired with corresponding terms in the target language, information and guidelines on usage. Most term bases are multilingual and contain terminology data in a range of different languages. |

| Translation memory (TM) | A TM is a database that stores sentences, paragraphs or segments of text that have been translated before. They support the localization process, dramatically improving the quality, speed, consistency and efficiency of every translation job. |

Nine things we keep in mind

Allocate enough time and resources, from the start

Resources are often scarce by the end of an investigation. When making an investigation plan, leave adequate time for translation, implementation, and quality assurance testing (QA). Involving a translator in the planning process will help ensure that these estimates are realistic.

If you plan to produce multiple language versions of a report or digital product, check that your team has the skills required to do so, or factor in external help. This could include, for example, web developers with experience in developing for Arabic script.

Keep people and place names in the source language

During the research process, people and location names that require transliteration between scripts, for example between Simplified Chinese and English, should be kept in the in the source language, ideally alongside the target language.

Names can be transliterated in multiple ways, making them hard or even impossible to trace back. This practice has heightened importance when an investigation contains sensitive biographical information such as the names of disappeared or missing people or civilian casualties.

One spreadsheet is better than many

If working in spreadsheets (e.g. for the translation of digital products such as websites and infographics), one spreadsheet with columns for each language is preferable to having multiple spreadsheets. Storing the data in one location helps prevent inconsistencies from occurring when, for example, one language version is updated but another is not.

Know the limits of algorithmic translation services

Human translators can respond to context in ways algorithmic translation services such as Google Translate cannot. In “Centering the ‘source’ in open source investigation” Libby McAvoy, a fellow at Mnemonic and WITNESS, reminds us of risks of relying on automated translation services:

There are known risks to relying on these tools. Slang does not always register in translation software: used for “drone” by some in Arabic, “zenana” (زنانة) means buzzing but translates to “dungeon” in English via Google Translate.

If you need to rely on an algorithmic translation service, at minimum be alert to the likelihood of such inaccuracies.

Provide translators with a glossary of key terms

Consistency and accuracy are important in translation. Investigators can help achieve both by providing translators with a glossary of key terms. A glossary is like a guide for translators, it provides them with accurate names, up-to-date information in the target language (if possible), and ensures that correct terms are used consistently. It is particularly important when multiple translators are working on the same project.

Glossaries are time-saving tools, too. Translators will spend lots of time researching phrases, names, titles, and background information before starting their translations. A good glossary compiled by the investigator will significantly shorten this process.

It is exactly such a deep understanding of the importance of accurate and consistent terminology which, in the late 90s, led Amnesty’s language teams to an online “term base” for internal use. AI Term — as our term base is known — has seen steady growth since its creation and currently features over 22,000 human rights terms in 10 languages. Its main purpose is to help ensure the consistency and harmonization of key terminology and definitions throughout our entire organization. AI Term is a useful resource for both language professionals and colleagues producing content in multiple languages.

Translators use a range of translation technologies to aid consistency and save time

In addition to term bases, “translation memories (TM)” are another translation technology commonly used by translation professionals.

A TM is a database that stores whole sentences, paragraphs or segments of text that have been translated before. They support the localization process, dramatically improving the quality, speed, and efficiency of every translation job.

Know that names of technologies can present a particular challenge

Unfortunately, some languages have fewer terminological resources than others. That’s the case for Arabic vis-à-vis information technology. For example, when translating a text about digital surveillance, it is not easy to find the relevant technical terms in Arabic. The Arabic translation team in Amnesty’s LRC, along with the support of their long-standing translators, have done intensive research throughout the years to introduce such terms to Arab audiences and keep these terms up to date whenever possible.

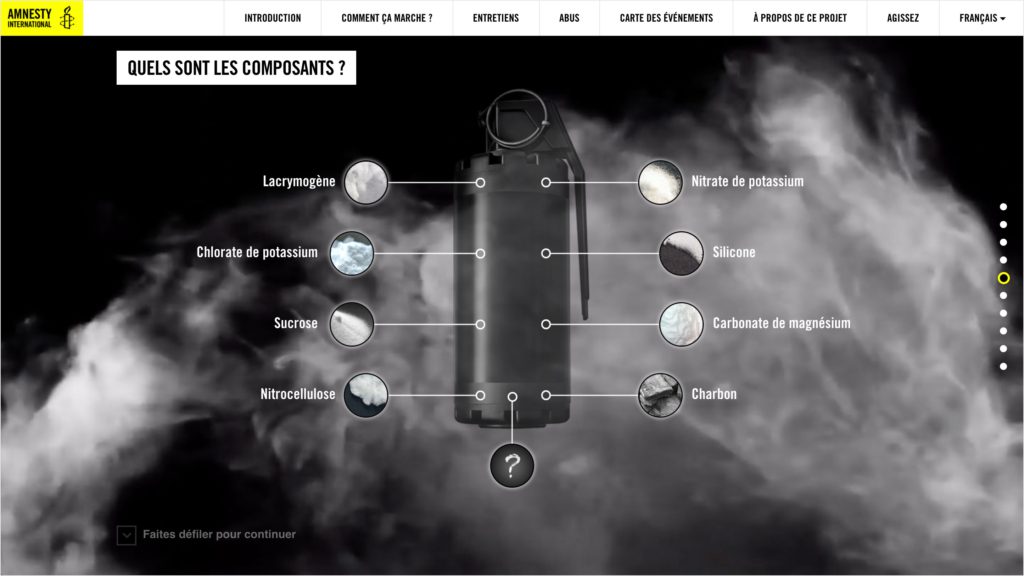

Provide a visual reference for digital projects such as websites and interactive graphics

Websites and interactive maps have lots of interactive components such as buttons, menu bars, and dropdowns, which are highly contextual. Investigators should provide translators with visual references such as wireframes or prototypes (that show the structure and functions of a website) and prototypes, as early as possible in the design process to help in translation.

Adapt interfaces and user test in the target language

One design does not fit all. When applying a translation to a website and application allocate resources to make adjustments. Through trial and error, the Evidence Lab has learnt to adapt the user interfaces and graphics it creates to work with target languages. Adaptions can be as obvious as flipping a left-to-right interface to right-to-left, or as subtle as increasing the size of buttons to allow for longer line lengths or merging text blocks to accommodate a different structure.

In general, when the localization process is from the Latin script to a more detailed script, such Farsi, the type sizes and line heights should be increased. User testing in the target language is key to ensuring that readability and functionality are consistently high across language versions.

Leave time, too, to fix technical glitches such as characters not displaying correctly in a target language script.